Gentrification in Pilsen and Its Impacts

Contributors: Connor Bentley, Hayley Mirabile, Sofia Johansson, Priya Rawal, Tori Choo, and Allison Ho

The Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago has become subject to increasing gentrification in the past three decades. El Paseo garden, founded in 2009 and located between Cullerton St and 21st st and Morgan and Peoria Streets, has been a healing space and a haven for community residents. But, according to leaders of the garden, developers have attempted to exploit the space to attract gentrifiers to the surrounding area.

Listen to Our Podcast

Transcription of Podcast

Priya: Welcome to the second episode of this podcast series exploring El Paseo garden in Pilsen, Chicago. We are students at the University of Chicago working with this garden for a class project, and participating in this conversation today is Priya Rawal, which is me, Tori Choo, and Sofia Johansson. Please be sure to listen to the other episodes in this podcast series for greater background and insight into the garden.

Within the broader Chicago area, Pilsen is often quickly associated with a city-wide stressor: gentrification. Though it is also well-known for its large Latinx population, especially Mexican, and the treasured restaurants, shops, and murals created by long-time residents, Pilsen has made headlines for its rapidly changing landscape and associated harms.

As students at the University of Chicago, we had the opportunity to work with the key community space in Pilsen, El Paseo Garden. Through conversations with leaders of the garden, namely Paula Acevedo, co-director of El Paseo, it became clear that gentrification is an issue that the garden and its community are constantly wrestling with. Therefore, we thought it would be beneficial to more deeply explore how gentrification in the wider Pilsen area is impacting and has impacted the garden, given that the garden has historically functioned as a vital cornerstone for the Latinx community in Pilsen to engage with each other and their roots. Our aim is solely to amplify the voices and work of those at El Paseo garden. We acknowledge that we are students with a high amount of privilege, no prior connection to the garden, and also extracted time and energy from those at the garden to put together this podcast. We hope that the podcast will assist in illuminating the tensions spaces such as El Paseo garden must contend with as its community and context changes due to gentrification.

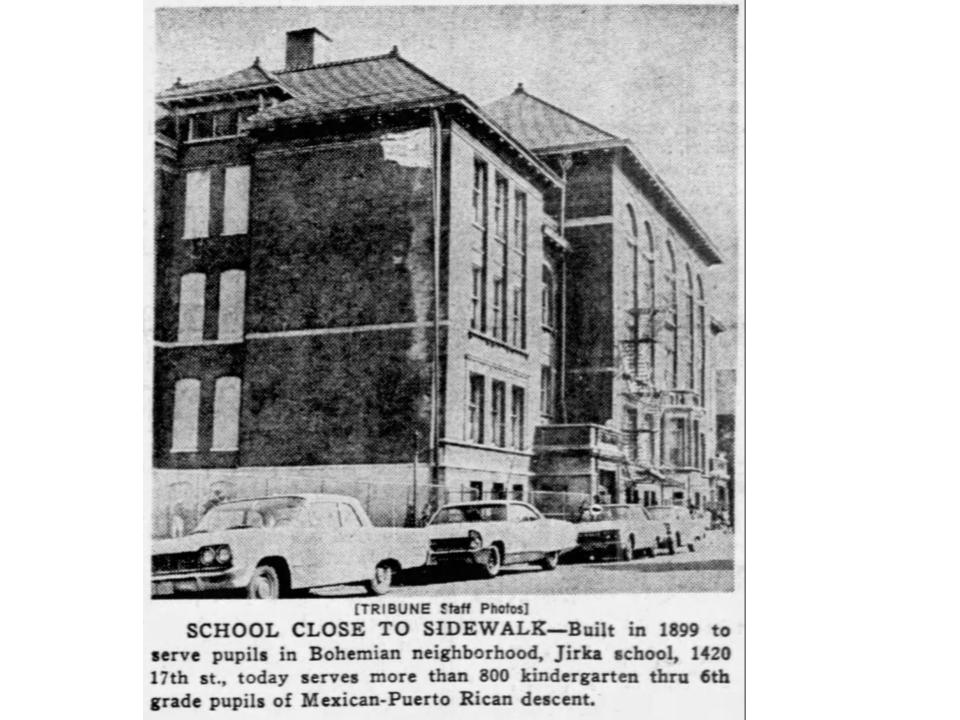

Sofia: We will begin with a brief history of the demographic shifts in Pilsen and the state of the housing market today before hearing more directly from a participant of the garden, the garden’s head manager, and the Pilsen Housing Alliance. Pilsen is located on the land of the Council of the Three Fires, including the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi nations. Post-colonization, 19th-century Pilsen was occupied by European immigrants primarily from modern-day Czechia and Poland. However, the neighborhood saw its first major shift in population after WWII, when many of the white residents fled the neighborhood as Mexicans moved into Pilsen after being pushed out of other areas of Chicago. Importantly, Mexicans came into the neighborhood before the massive white flight occurred. Pilsen became the first majority-Latino community in the city. But not long after this demographic transition, Pilsen was labeled a slum by the government and white residents of Chicago. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, residents of Pilsen fought hard against proposed development projects and blighting schemes that likely would have spurred what we now consider to be gentrification. Particularly in the 1970s, there was an immense amount of grassroots organizing for a variety of social justice issues. However, in the 1990s, activists faced a large battle ahead as the mayor of Chicago appointed a pro-gentrification alderman, Danny Solis, for the 25th ward. During this decade, thousands of public housing units in Pilsen were demolished for mixed-income housing and development of middle-to-upper income housing proliferated. These housing projects further attracted real estate developers and fast-tracked gentrification in the neighborhood, especially on its east side, where the garden is located. A widely-cited 2016 report on gentrification in Pilsen, by Betancur and Kim, aptly noted that though development largely stopped during the Great Recession, “investors acquired foreclosured homes and short sales, renting them while awaiting the opportunity to sell them to a new wave of gentrifiers.” This move affected not only the east part of Pilsen, but began trickling into the west side as well. Additionally, Betancur and Kim state that contrary to statements that Pilsen was only Latinx-on-Latinx gentrification, much of “the evidence suggests that developers, capital investors, and gentrifiers have been predominantly White”. That statement is certainly in line with the most recent demographic data of the area, taken from the Chicago Health Atlas.

Priya: El Paseo garden was formed in 2009, during the Great Recession, and at the same time as the development of three affordable housing buildings next to the garden. The percentage of white people in the Lower West Side community area has increased by 9.86% since then. At the same time, the percentage of Hispanic/Latino residents in the Lower West Side decreased by 15.09% between 2009 and 2021. The age and family composition of residents has changed significantly as well. Paula Acevedo notes that the number of children in the neighborhood, or families with children, has greatly decreased during her time at the garden. Now, those coming into the neighborhood seem to be mostly young, white professionals without children.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the current median household income of the white population in the Lower West Side and that of the Hispanic/Latino population are markedly different. The median household income of white people in the Lower West Side was $88,873 between 2017 and 2021, an increase of nearly $34,000 since 2009-2013, while the median household income of Hispanic/Latino in the Lower West Side was $53,954 from 2017-2021, up only $13,000 since 2009-2013. Moreover, the median house sale prices have been rising much more rapidly than median household incomes. In the Pilsen historic district, the median house sale price in 2023 is $449,000, while it was $365,000 just five years ago. In East Pilsen, prices have increased even more dramatically, with a 2023 median sale price of $608,750, almost triple the median house sale price in 2018, which was $220,000. Acevedo notes that this is a huge issue, primarily because the price of affordable housing units is not based on median household income or wealth for different groups or even the smaller geographic region of community areas, but the greater Chicago area as a whole. Therefore, a key issue that complicates this even further is that affordable housing is not necessarily affordable, and residents are being displaced even from affordable housing units.

Tori: As noted, the media has certainly picked up on the story of gentrification in Pilsen, and residents have been loud in voicing their concerns as well. A scan of recent Tweets about gentrification in Pilsen quickly brings up thoughts from aggrieved residents and former residents. Many are upset about the displacement of the Latinx community and harm caused by the new white residents. For example, a Tweet from May of 2023 by user @ally_bae stated “you can visit and shop in Pilsen and support the economy of pilsen without adding to the gentrification ie don’t sign a lease in Pilsen if you’re white, 2500 for a 2 bedroom is already criminal enough.” Another Tweet from 2018, from user @tired_butwoke, responding to an announcement that Forbes named the neighborhood one of the coolest in the world, wrote that the announcement was a “red flag that Pilsen is going to get hit even harder with gentrification.” In May of that same year, resident activists held a protest advocating for a community benefits agreement, with signs such as “the hood is not for sale” and “new here? Our culture is not your entertainment.” Twitter User @kofiademola wrote that “gentrification is colonization” and that they should “with [their] comrades in Pilsen as they shame the culture vultures who are pushing out the Latinx community!”. Other users voiced distress over former mayor Lori Lightfoot’s introduction of a landmark ordinance that would have designated Pilsen as a “landmark district,” likely leading to greater attraction and therefore gentrification in the neighborhood if no other housing measures were to be pursued. Eventually, the proposed landmark ordinance failed. Another Tweet from December of 2022, from user Ricardo Gamboa seems to address some media claims that gentrification has been good for Pilsen, stating “so what has this ‘cool’ gentrification done for Pilsen’s [Mexican] American community besides give them opportunities to make white people richer by patronizing their establishments? What has all this ‘development’ done besides disappear the existent Mexican American community?” Through Tweets, protests, community conversations, and more, residents have been actively expressing their frustrations with continual gentrification for a long time. Certainly, these frustrations are shared by members of the garden as well.

Sofia: Daisy Morales, a member of the garden since 2019, recently expressed her experience with increasing housing costs and development to a fellow classmate. Daisy has lived in the neighborhood for the past six years, but originally lived in Pilsen over 25 years ago, and has lived in Chicago for a total of 41 years. When Daisy first lived in Pilsen more than 25 years ago, she says that the neighborhood was mostly Mexican, and she already saw a huge difference when she moved back 10 years ago. In 2015, she got married, but had to move to Little Village because she and her husband could not find an affordable apartment in the neighborhood. When she moved back, she was able to find an apartment for just herself with an owner that kept rents low, due to the age and condition of the building, as the building had not been remodeled. However, in January of this year, 2023, an investor bought the building, and has plans to remodel it and rent it out for three times what she is paying at the moment. Daisy faces court with the investor if she does not move out or find a way to pay.

Daisy: But now that I have to move out of there, for an apartment like the one I’m renting, it’s double to triple what I pay in rent. So I’m going to have to get another job to be able to pay rent if I decide to stay in the neighborhood because I might just have to move somewhere out of the neighborhood to be able to pay a little bit less rent.

Sofia: It’s not just Daisy and her building facing greedy investors. Both Daisy and her daughter noted how visible the gentrification in Pilsen and greater Chicago is today, and that prices just keep rising.

Daisy: Gentrification has brought, has skyrocketed rents and the Latino community that doesn’t make as much money as other people, they have to, we have to move out to far away neighborhoods.

Karla (Daisy’s daughter): I’ll add to that, that gentrification is very in our face now. It’s not hushed. I feel there is a constant reminder. I feel like everytime I leave the house, I’m like ‘I didn’t see that there, what in the world is this?’ It’s things just popping up so constantly, and I feel like I can’t go a week without taking a walk down 18th Street, and seeing another random shop. Aside from seeing all these moving trucks so constantly, you know, and seeing someone else pop in, another professional, with their fancy car, and seeing the buildings next to us.

Daisy: We’re one of the last buildings that was sold in our block. Even Little Village is getting really expensive now.

Sofia: Though they currently live in the same building, they will have to separate due to the new investor. Daisy expressed her deep sadness at the thought of moving neighborhoods away from her daughter and grandchildren.

Daisy: I feel really sad because I’ve always been close to my daughter and my grandchildren.

Sofia: In response, Daisy’s daughter [Karla] explained her frustrations with the rising impacts of gentrification.

Karla: It’s like ‘oo you guys have created a nice little neighborhood, we want it, give it to us’ that’s what it feels like. Take all your culture and all the shit that you’ve created for yourselves. Whether you are accepting of the people there, and you appreciate it, and you’re coexisting beautifully, it’s still gentrification.

Sofia: But Daisy says that the garden, despite its changing demographics due to gentrification and the changing identities of those in the neighborhood, is still a vital community space for all.

Daisy: You can see the changes in the garden too but, then again, I honestly see a beautiful mix at the garden.

Sofia: When asked what they think should be done about the harms of gentrification, Daisy turned most of her attention and call for action to the municipal government.

Daisy: Gentrification is something that’s created by the leaders, no? Of this city, by the people in power, by the people in money, with money. This is creating war in between us and the white people, that’s the way I see it. The leaders in this city, you know, the governor and everybody else that’s involved with them, they should do things where they take buildings, and… more buildings because I know that there are a few organizations out here taking older buildings and remodeling them and renting them at a lower price.

Sofia: Daisy returned back to her current situation, and stated that the low income housing available is not actually low income, and that many people do not even make enough money to qualify for “affordable housing.”

Daisy: Still low income homes are not low income because I didn’t qualify for a low income apartment, because a studio was, they had a studio available for me, for almost $1100. This is through a low-income organization of this neighborhood. And I was like, aren’t you guys supposed to help, people like me, that don’t, that I’m not gonna have a place to live soon? Where I’m gonna have to like, throw all my stuff out and go stay in my daughter’s living room? And they were like ‘you don’t qualify because your income was so low,’ and they’re like, ‘well it’s just so low that we can’t qualify you for an apartment.’ And I was like, what in the world, how do I get help? And they said ‘oh you gotta go through the Chicago Housing Authority, but that’s gonna take even longer than with us.’ So I was like ok, and she says ‘I don’t recommend for you to stay where you’re at because this guy is gonna end up taking you to court and it’s gonna be harder for you to rent any place because this is gonna go on to your credit report.’ So even low income housing, it’s really high for people like me.

Sofia: Daisy’s daughter added in, stating how surprised she was that she qualified for low income housing, because she thought she made quite a bit more than what may be the cap.

Karla: Low income housing, and the help that they have for that, just doesn’t really seem to be realistic for the majority of people that truly need it. Lucky for me I was able to meet the qualifications and I’m getting my foot in the door. And I’ve been very hesitant about applying because I’ve said for years I don’t feel like I really need the low income housing, right? Because I make decent money and I feel like it would be more fair for someone like my mother and someone else not making above fifty thousand dollars, to be able to get the spaces and the help. And unfortunately, even if I’m not applying, there’s people, again tons of people, that really really need the help, and they wouldn’t be able to get it anyways.

Sofia: Daisy interjected, however, and told her daughter that:

Daisy: You still need the help, you have four children, and an apartment for you would be twice the price that you’re paying right now.

Sofia: In the end, the two truly just expressed their confusion, frustration, and anger with how the city was handling gentrification and the low-income housing stock.

Karla: It’s really not making sense. I feel like it’s just not making sense, you know? Maybe I don’t know how they go about it, but to me the low income housing and the help is not adding up, and it’s not making sense. And it’s not really helping people. We have another friend in need, her and her mother, disabled and elderly, and they don’t qualify. or they’re not prioritized, that’s what they were told, right. And these people are really in desperate need of somewhere to be, somewhere to stay. They’re basically homeless. And it’s impossible for them to find somewhere. I just feel like they need to do a better job at making things available to the people that truly need the help.

Priya: Paula Acevedo, co-director of the garden, shares this frustration. Furthermore, as a manager of the garden, she sees first-hand how the garden is being impacted by gentrification, and also how it is being used to spur gentrification further.

Acevedo: Developers or realtors or listings and how they list the garden as an amenity. And I literally have seen posts where it’s the views of the inside of the house and you’re swiping, and then it was like a picture of the garden.

Priya: In the past, Acevedo has personally reached out to developers to tell them to stop listing El Paseo as an amenity to attract people to Pilsen. However, she notes that she doesn’t have the capacity to call out all realtors using pictures of the garden, and that they have no responsibility to take anything down. But Acevedo feels especially inclined to stop this kind of exploitation because El Paseo is not run on city funds, but rather through the hard work of volunteers like Daisy, who are already struggling to find a way to stay in the neighborhood due to gentrification.

Acevedo: Cause you know, this isn’t your typical park where it’s like a taxpayer amenity, so to speak, right. Maybe very, very indirectly because our Land Trust does receive like city support and funding for all the over 130 gardens that they have throughout the city. But as you know, so indirectly because NeighborSpace receives funding and they are the legal entity that kind of owns the land and ensures it. But besides that, the day to day, the maintenance and everything is from the volunteers in the community. And so, you feel as if that is exploited, right? Your hard work and labor and efforts that are meant for your community are being exploited for profit, essentially. And that’s the case throughout the neighborhood as people, you know, Pilsen’s really become a neighborhood known for its culture and art. And so the artists in the neighborhood are also, you know, feeling exploited. You know, all the murals that we have that were created from, you know, many times the, the art and murals that you see, the, especially the older ones, they’re a form of activism in a form of expressing yourselves and telling the story and, you know, of the community, of the people. And so it becomes, you know, what happens when those people that create that culture and create these amenities, And, you know, I’ll say amenities in quotes. What happens as they’re being pushed out and as that story and that culture is being kind of erased. So then what are they gonna promote?

Priya: But as stated prior, and despite the best efforts of community members such as Acevedo, gentrification has been an ongoing issue in Pilsen. Acevedo notes that the shutting down of the coal plant in 2013 likely spiked gentrification in the neighborhood further. Notably, that shutdown was won by long-term resident activists of Pilsen who had long suffered the environmental injustice of the coal plant. But the worst bout of gentrification has occurred after former mayor Rahm Emmanuel announced the Rails to Trails project, and the four miles of trails that would connect the garden to Little Village.

Acevedo: And so that immediately spurred so much speculation. People swooped in and so much development happened. And to this day, the land is not even owned by the city. It’s still in the hands of the railroad. And so it doesn’t matter if the path is there or not, the effects, the impacts are already felt the been, you know, felt. And the wood would be the east side of the garden. That block has a bunch of single family homes. We have the warehouses across the street that were converted and developed. You could see the increase in property values everywhere. And so it’s become pretty unaffordable. And then with the pandemic, that was really a huge hit, I feel like, everywhere, right across the world. But it was a very huge hit because people weren’t able to, they, they weren’t able to keep their homes. And they wouldn’t be able, they weren’t able to pay the mortgages, there was a lot of foreclosures. And so even those who did own their properties weren’t able to keep them. And so many people are displaced and they have to move to more affordable areas, which many times are, you know, disinvested neighborhoods that don’t have all the resources and like, “amenities” as communities. And so they are moving to other neighborhoods that may have increased crime, you know, have less resources. And overall you can see in the data, that there are less families, especially of Latinx, Hispanic backgrounds. And the schools are under enrolled as well. And so you can see that there’s an uptick of smaller size households, different demographics. So the changes are there. It’s on paper.

Priya: When asked about how gentrification has specifically affected the community at El Paseo, Acevedo echoed many of Daisy Morales’ sentiments.

Acevedo: So we are along three affordable housing apartments, so that’s supposed to kind of mitigate those effects. Right. However, even the definition of affordable is not accessible and so we’re people are even being displaced from the quote unquote affordable housing. And so we are losing families and seniors that have been living in those buildings since they were built in 2009. And, and those are supposed to be the people who are protected. And, you know, we always say that we do aim to serve the residents in those buildings, and kind of keeps us rooted in our mission, right? To be able to serve those who need it most and to be able to. Like we are literally their backyard. And so we always said that that would keep us rooted in our mission and it’s, it’s sometimes discouraging when we see that even those buildings have a lot of transition and become inaccessible for a lot of families and seniors as well. And so it is, there’s a lot going on. There’s less kids that play in the garden. There used to be a group of kids that were always playing in the garden. It’s their, like I said, their backyard. There’s kind of less of that. And, you know, we have lost some, you know, seniors as well. Like I said, from being, the rent going up too high. And so if you’re not section eight, if you’re not on the housing voucher, then your rent will go up in the affordable housing. And so, That’s kind of what happens. And then we mentioned on the other side of the garden is just all single family homes.

Priya: Similarly to Daisy Morales, Acevedo states that the changing community at the garden, though at times distressing, has not been negative. She aims to make clear that the garden is welcome for everyone, though their focus may be on making sure that those for whom the garden is essential community space are prioritized.

Acevedo: You know, it is a transient community. A lot of the active volunteers are, you know, they’re not indigenous Pilsen residents. But they contributed a lot, and the garden is a welcoming space for everyone. But however, they acknowledge, like they’re here for a hobby, for a leisure time, they’re not here to want another job. Right? And so our volunteers, you know, we’re trying to grow capacity right now in order to balance and become more equitable is basically we need to create jobs. And so if you’re involved at El Paseo, you have those kind of aligning principles, right? Because if you’re somebody that’s just interested in growing your heirloom tomatoes and gardening for yourself, that’s not what we are. We’re not an enclosed allotment garden where you can just, you know, we’re not the space, the growing beds, the food beds, they’re all kind of open to the public. So if you’re not there to connect with people and to create community and, you know, to support one another and support the overall garden and the mission, then that’s kind of already weeding out some folks that don’t have those principles, they might quickly learn and just not show up anymore.

Priya: And Acevedo, like Morales and her daughter, clearly expressed that a priority in the community is ensuring truly affordable housing in the face of neighborhood changes. She notes that though housing must increase in quantity and quality, namely that units must be fit for larger families and redeveloped from the old stock, they must also be made affordable.

Acevedo: So instead of seeing homes as a commodity, we need to see it as something we need to protect as a right, as a human right, not a commodity. Just like we said, green space is a right. It’s not an amenity. But then you also see the affordable housing that exists now and people are being displaced from the “affordable housing.” Like the affordable housing isn’t targeting, it’s not gonna target the families, the low income families. It’s gonna be targeting people who are at moderate, medium, you know, income levels. So once again, you’re still gonna, it’s, is it gonna solve anything? Is it just like, it’s gonna be very curious. It’s gonna be some section eight and everything else is gonna be targeted towards medium income levels, right? Not necessarily low. So to me, my biggest hope is that the Pilsen Housing Co-op and co-ops can expand because to me, co-ops, they also target mid medium incomes too. It’s not necessarily low, low income, but co-ops do give the option that you will at least own that part property. You will co-own that building and you can pass that down and that could, you know, pass it down to your descendants and it will build some equity. And that was secure. You know? That you are able to age in place in your community. So co-ops to me are a really great solution. However, I still think there’s gonna be a lot of people left behind that are like low income families and so there’s, you know, it’s not gonna solve everything, but we’ll see. There is not enough affordable housing. It’s the size of units, like if you’re creating affordable housing that’s like one bedroom that’s not for families, you need like three plus bedrooms for families, right? So it is the physical, you know, amounts and makeup of affordable housing units, but overall the city’s housing system is just, it’s just messed up honestly, because they base affordable, the definition of affordable, off the average median income, the AMI off I think a larger swath. And I’m not a hundred percent, I don’t wanna misspeak, but I think it’s basically the larger, I don’t know if it’s the county or even a, a different larger swath. But the Cook County is a wealthy neighborhood, so if they’re taking the average media and income that’s not targeting what the needs of a specific community are, that’s a huge swath. And so that’s where you have that skewed what, what it means to be affordable. What is the number, amount of what defines affordable because it’s not, it’s not accessible. Affordable for who? Right? And so the larger system is just a mess.

Priya: Acevedo also pointed to the larger systems of redlining, discrimination, displacement, and systemic harm that have been operating violently for decades in the lead up to widespread gentrification.

Acevedo: You know there’s been such disinvestment for such a long time. And even the history of how CHA was introduced or created, it is not a nice pretty history, right? It’s a notorious disinvestment in racism of redlining and displacing people and imminent domain and you know, like, think about all the black wealth that there was, and they essentially had their homes taken from them and ‘Oh! but you know, we’re taking your home for this university or this highway, but you get to be in this, this building.’ So there’s just like a really dark history of housing and disinvestment and racism in the city of Chicago. And so there’s a lot of catching up to do and it’s not, you know, it’s not gonna be easy, but it’s like how do you change this larger system?

Priya: Acevedo got personal with one story of a couple at the garden who were deeply impacted by gentrification in the neighborhood, recently being displaced from their home in their late 80s.

Acevedo: Some of our seniors, a couple that has been involved and lived in the senior residence, the apartments by the garden since 2009, the first resident, they were not section eight and they got displaced. But not even a month in, he passed away. He was 89 years old and he passed away, and I literally just like last week, went to his memorial. And so you kind of think ‘you’re not supposed to move seniors!’ That’s not good for their health. It’s just frustrating. Like you really can’t do more as a nonprofit developer, you can’t do more to protect the people in the community? Like you cannot find some kind of way to subsidize? You couldn’t just give ’em a couple more months? And, you know, so it’s like I’m mad. But like I said, the seniors, they’ve been through it ,and it’s just the way it is, and they don’t hold on. Like they’re just like, ‘yeah, we were displaced when UIC was built, when the highways were built and this, and this and that,’ and yeah. And I’m just like, ‘what?’ This is not right. It’s not right. It wears people down. Like people are too busy trying to survive and figure out where they’re gonna live or how they’re gonna, you know, do anything to fight for their rights to speak up or to have the capacity to speak up. And so that’s the classic. Keep communities divided, keep people disinvested and the rich will be rich and the poor will be poor. And like that’s just capitalism, honestly.

Priya: Bringing it back to the garden:

Acevedo: Part of the beauty of the garden is that it feels like family, right? You’re creating relationships like meaningful relationships with people. And so it’s just really hard when you see this kind of stuff happening to those people you built relationships with. It’s a very diverse space. You will, you could go to the garden and just see so many types of people, new residents and legacy residents and people from outside the community. Like, literally it’s become a destination for, um, there’s people from the suburbs coming to the sound healing meditation and things. And so it has become a destination. To us, it’s not what we ever intended. Like the word is out. I do get a little bit when people, the new, a lot of our new members, they’re like, ‘we moved over here because we wanted to be close to the garden.’ To me, it’s like ouch. Ah, yeah. But, so, it is challenging. We really bridge the community of all, all backgrounds of the activists, of the new residents, of the other community leaders. I think that everybody does appreciate it and has respect for the work that we do, and so that really makes me happy. Just like that, to me that is good. Testimonial and accountability for like, ‘Oh, okay, good. We’re not being seen as like–’ although I’m very hard on ourselves, but I mean, I think that people, because we’re not the cause of the gentrification, right? It’s this larger system. And so that’s like our gentle reminders I have to have for myself is that like, this would be happening with or without our work. And yeah, it is a nice amenity, but. I think that it’s, you can’t, it’s, it’s the exploitation of community, people who make the community better, who fought for the coal plant to shut down and who fought for the school, who fought for the library. Like it’s exploitation of everybody who’s poured their heart into the community to make it what it is, really.

Tori: The Pilsen Alliance started in 2014. Since then, they have made impressive strides in supporting the Pilsen community and combating gentrification within Pilsen. In 2015, they successfully fought to keep four schools open in Pilsen. They have also worked with other residents and community organizations to force the shut down of the Fisk Coal Power Plant in Pilsen. The Pilsen Alliance has also received the Barbara Grau Award for Excellence Housing Justice Advocacy work. And from 2019-2020, they helped stop the Pilsen Landmark Ordinance Proposed by the Department of Planning and Development. Now the Pilsen Alliance consists of about 60 members, and we had the chance to talk to one of them, Javiar Ruiz. Ruiz started off as a volunteer community organizer and currently serves on the board of directors. Ruiz is 27 and has lived between Pilsen and Little Village his whole life. He describes noticing gentrification in Pilsen as becoming a real problem when he was in his teenage years, and he got involved with the Pilsen Alliance in 2014.

He describes the Pilsen Alliance as working on a mixture of policy and civic engagement. While he thinks affordable housing is good, he describes it as “putting bandaids on bullet wounds” and is working to create sustainable policy for more permanent solutions. He outlines a few policies the Pilsen Alliance is advocating for that he believes will put an end to gentrification. The first one is rent control. Right now, rent control is illegal in the State of Illinois. While some politicians have proposed policies to put an end to this, nothing has been successful. Legalizing rent control has been a large focus for the Pilsen Alliance:

Ruiz: For example, in 2018, we did a yes or no ballot question, should the state of Illinois implement rent control? And that one got overwhelmingly 70% of the neighborhood voted yes.

Tori: He also wants to see a Just Cause Ordinance

Ruiz: We’re trying to get a just cause to evict ordinance in the city of Chicago. Basically, the landlord has to give you a good reason if they want you out. Right? Now, unfortunately a landlord could just tell you, hey, I want you to leave. And that’s perfectly legal.

Tori: Another policy they are working with is the Healthy Homes Ordinance. Ruiz describes how as prices increase, small land-lords are penalized by city inspectors for not maintaining properties to meet the city standards. These smaller landlords are then forced to sell their properties.

Ruiz: What we’re proposing is like a healthy homes ordinance where we could give grants to small landlords where they could do general repairs and maintenance so that way they’re not forced to sell.

Tori: Another goal of the Pilsen Alliance is to Push back on the TIFF expansion.

Ruiz: TIFF is like a district within the city where property owners that live within the district got to pay an additional tax. And the idea being it’s supposed to go towards construction projects, like building a grocery store, building roads, building schools. Right? A lot of the time, unfortunately, it’s used as a slush fund for developers, realtors, corporate welfare. We’ve seen Walmart and Target get free money from the government, from the city of Chicago to build, to subsidize their expenses.

Tori: The Pilsen Alliance is now working to put a pause to expanding TIFF in Pilsen. The Pilsen Alliance is also drafting policy for a social housing pilot. Ruiz describes the social housing pilot as a better alternative to affordable housing. The concept is creating housing that is shielded from the forces of the market. Renters would, at all times, pay 30% of their income, regardless of how the housing market fluctuates around them.

Ruiz: The idea being it’s supposed to be all incomes. All incomes live together. You know? Right now, we’re still in the process of drafting it, further explaining it. Right. In the near future we’ll have something more concrete to put out there. Yeah, but for the time being, that’s sort of what we envision.

Tori: Ruiz also told me how a large part of his work is efforts to boost community engagement. The Pilsen Alliance works to educate the community on pertinent topics.

Ruiz: We’ve held events informing the community about gentrification, rising property taxes, doing tenants’ rights workshops, lobbying for rent control in the state of Illinois.

Tori: While they are not allowed to endorse public officials or get involved with electoral politics, they try to promote civic engagement and voter turnout more broadly.

Ruiz: I mean, you see voter turnout is always historically low. Usually the communities that have the lowest voter turnout and civic participation are the ones that get smacked the more.

Tori: He explains how difficult of a process it is to get community members engaged politically

Ruiz: You’re not gonna like the cynic that’s been a cynic for 20 years. You’re not going to make them, like, a super engaged constituent, like, in a week. Right? It takes time. You got to build relationships with them. You got to talk with them, get to know them. It is like a hustle and grind.

Tori: I asked Ruiz how El Paseo and the new Rails to Trails project has impacted his work and gentrification in the community.

Ruiz: We want to have nice things. We want to have green spaces and gardens, but it shouldn’t come the trade off being like, okay, everybody’s rent is increasing.

Tori: He believes people have a right to green space.

Ruiz: Every neighborhood in the city of Chicago should be entitled to green spaces and nice things.

Tori: He believes that policies need to be in place, like the ones we outlined earlier, to enable access to these amenities without raising rents and displacing people. I ended my interview by asking if he thought gentrification would actually be solved. His response:

Ruiz: I think we can. I think it’s doable. I would say personally, if it wasn’t, like, for the Pilsen Alliance, pushing back against development, like, luxury development, the neighborhood would be different.

Sofia: Thank you for taking the time to listen to this podcast and hear voices from El Paseo garden. We hope you enjoyed, and strongly encourage you to tune into the other episodes in this series.

History of Pilsen: Rise of Gentrification

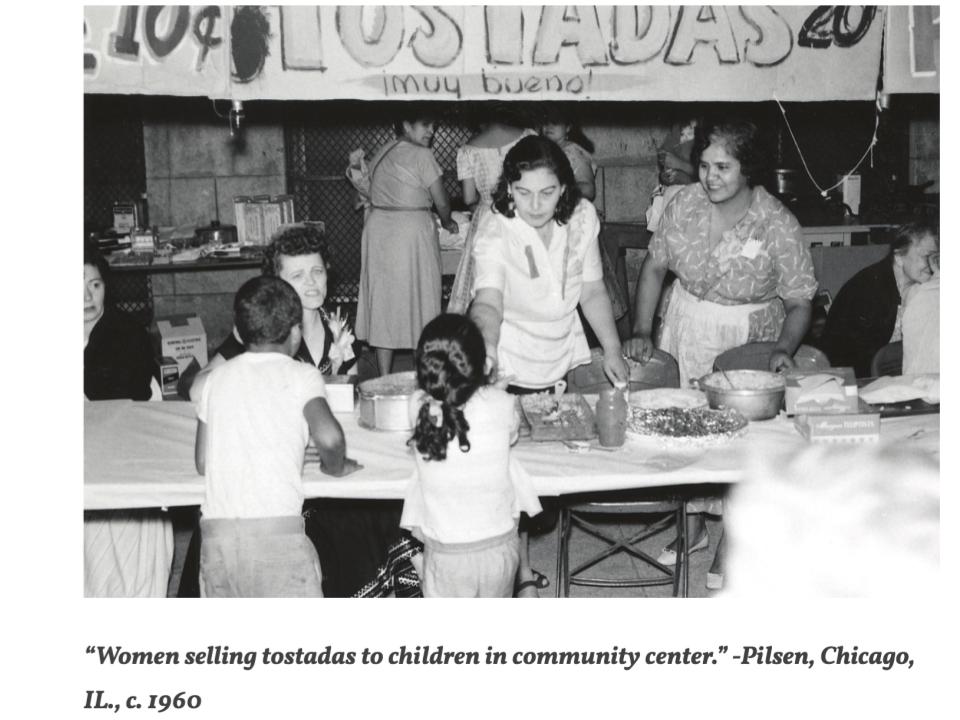

Pilsen is located on the land of the Council of Three Fires, composed of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi Nations. In the late 1800s and through the early 1900s, the neighborhood was primarily occupied by Polish and Czech immigrants. After World War II, Mexicans began to move to Pilsen after being displaced from other areas of Chicago. Once construction of UIC started in the early 1960s, thousands of Chicagoans, many of them Mexican, were displaced from their homes and came to the Pilsen neighborhood. As was happening throughout the Chicago area, white flight rapidly occurred as the European immigrants fled from Pilsen, and the neighborhood became the first majority-Latino community in the city.

Image from Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1966.

Image from Seven Settlement Houses-Database of Photos (University of Illinois at Chicago), University of Illinois at Chicago Library Special Collections and University Archives.

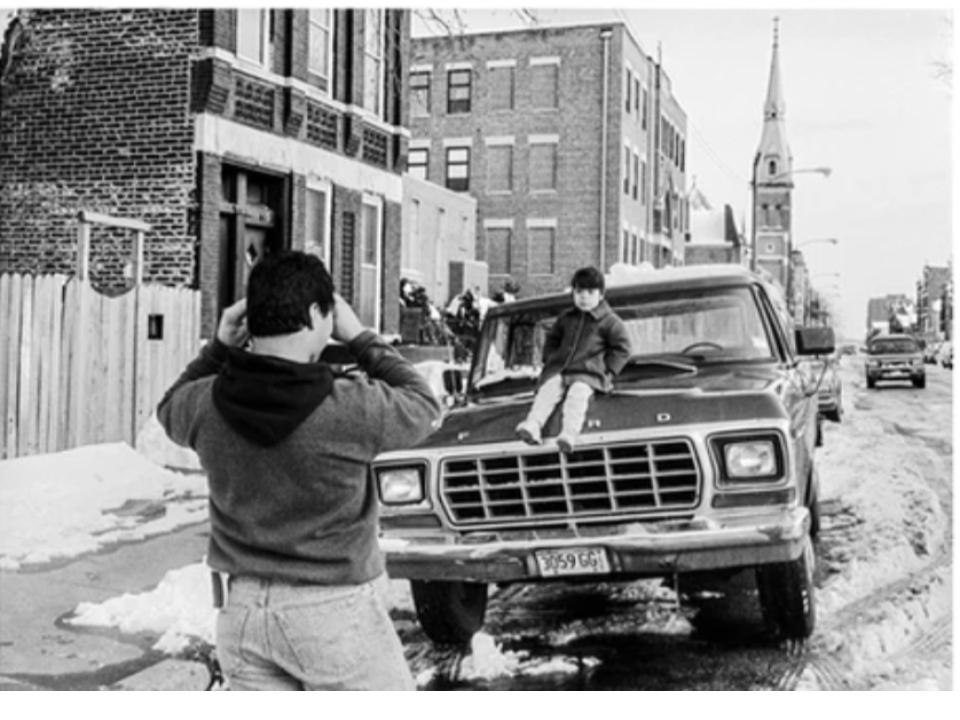

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, residents of Pilsen fought hard against proposed development projects and blighting schemes that likely would have spurred what we now call gentrification. However, in 1996, activists faced a large battle when the mayor of Chicago (Richard M. Daley) appointed a pro-gentrification alderman, Danny Solis, for the ward encompassing Pilsen. During this decade, thousands of public housing units in Pilsen were demolished for mixed-income housing and development of middle-to-upper income housing proliferated. For example, 3,596 public housing units became a mixed-income community, and the development of University Village, a project between the City of Chicago and UIC, also added more housing for those with higher incomes. These housing projects further attracted real estate developers and fast-tracked gentrification in the neighborhood, especially on its east side. A widely-cited 2016 report on gentrification in Pilsen (Betancur and Kim) aptly noted that though development largely stopped during the Great Recession, “investors acquired foreclosures homes and short sales, renting them while awaiting the opportunity to sell them to a new wave of gentrifiers.” This move affected not only East Pilsen, but began trickling into the west side as well. Additionally, Betancur and Kim state that contrary to statements that Pilsen was only Latinx-on-Latinx gentrification, much of “the evidence suggests that developers, capital investors, and gentrifiers have been predominantly White.”

Photograph from Akito Tsuda, Pilsen Days: A Neighborhood Story, 2022.

Cullerton and Peoria St, Image from Imgur, Fifty Changes in Pilsen over Fifteen Years.

Today, Pilsen looks much different than it did even just a decade ago, and that’s because of the gentrification in the area. As resident Moises Moreno said, “Because of [the] richness of history and culture it’s also easy for folks that want to capitalize on that, to try to make profit off of our culture, and the land itself.” Measured between 2017-2021, the median household income of Hispanic/Latino people in Lower West Side was $53,954, while for white people, it was $88,873. The percentage of white people in Lower West Side increased by 9.86% between 2009 and 2021, whereas during that same time frame the percentage of Hispanic/Latino people in the area decreased by 15.09%.

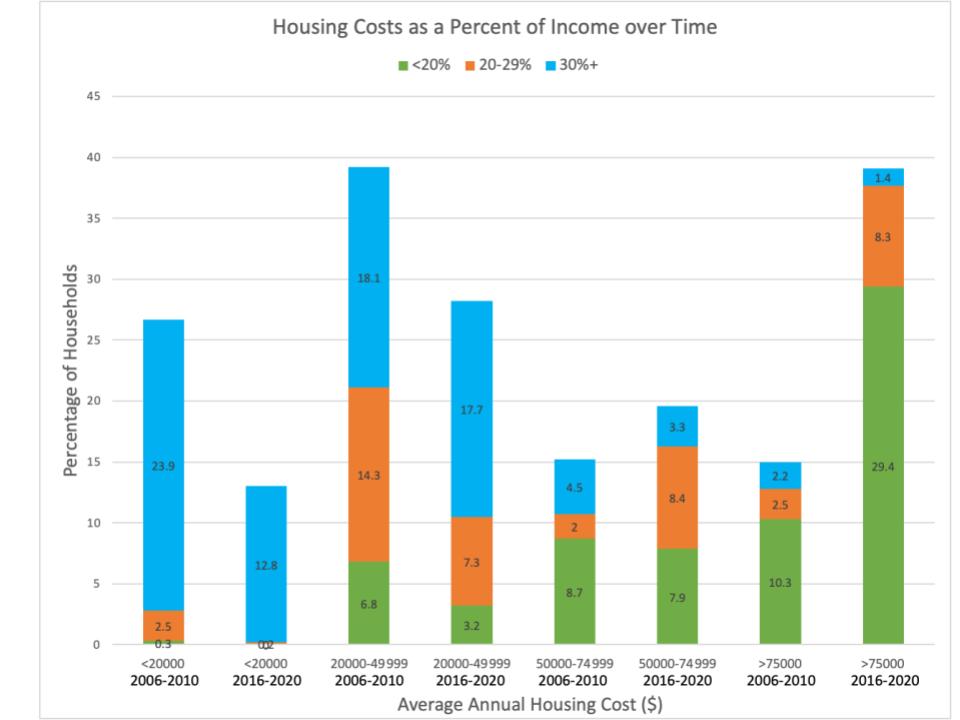

Within the last 20 years, as Pilsen has become increasingly gentrified, household income has risen significantly as lower-income individuals have been displaced by wealthier individuals moving into the neighborhood. According to the American Community Survey, the median household income in Pilsen was $41,095 from 2006-2010 and $59,889 from 2016-2020, with both numbers adjusted for inflation. This nearly 150% increase in median income did not come from an increase in wealth in those native to Pilsen, but rather from the new population of largely white millennials. At the same time, housing costs have increased with new developments and higher demand stemming from the influx of new residents willing to pay higher prices for housing. While the median gross rent in 2000 was $820, that from 2017-2021 was $1,384, with both adjusted for inflation. Housing costs similarly rose, increasing from a median value of $185,692 in 2000 to $317,764 from 2017-2021. As the graph below shows, the burden of these changes fell disproportionately on lower-income individuals, as they increasingly had to spend more than 30% of their household income on housing while the share of more affordable housing greatly decreased.

Source: 2006-2010 and 2016-2020 American Community Survey five-year estimates. *Excludes households with zero/negative income, and renting households paying no cash rent.

Pilsen Policies: Change Through the Government

Planning El Paseo: Plans and Studies 2006-2017

One major tool in the planning process for El Paseo trail and garden has been the Pilsen Quality of Life Plans. The first iteration of the plan was published in 2006, and outlines various strategies to improve life in the neighborhood. These include expanding housing options for Pilsen residents and strengthening the neighborhood economy. This plan also proposed El Paseo: a multi-use trail and mixed-use commercial corridor along an abandoned stretch of railroad. The plan specifically targets what is known as the Sangamon corridor, or the stretch of abandoned tracks between 16th Street and Cermak Road along Sangamon Street.

Initial plan for El Paseo, depicting varying land uses and potential residential and commercial developments. Source: 2006 LISC/Chicago.

This plan incorporated various recreational improvements, linkages between commercial corridors on 18th and Cermak, and provided affordable housing with the Casa Maravilla and Casa Morelos senior housing buildings, which currently sit west of the garden. The plan also envisions a development on Peoria Street between 16th and 18th streets, which currently sits vacant as city-owned land.

The second Quality of Life Plan was completed in 2017 and focuses primarily on housing and health in relation to gentrification and El Paseo. The plan’s housing goals focus mainly on the actions of the PLUC with the 21% Mandate and ARO Pilot. Additionally, the need for greenspace is emphasized especially in relation to health, and the plan sets goals for increasing access to greenspace for recreation and gardening, expanding programming at El Paseo community garden, and developing an advisory committee for future development of the El Paseo trail.

Aside from the Pilsen Quality of Life Plans, various other municipal agencies, private developers, and local non-profit organizations have completed studies of the area, typically assessing the rails-to-trails project. These primarily included the city of Chicago’s Departments of Planning and Development (DPD) and Transportation (DOT), the Chicago Park District, and the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP). Many of the plans created by these agencies reveal a common thread of inadequate access to open space in Pilsen, with the per capita distribution of open space measuring 1.54 acres per 1000 Pilsen residents, compared to a benchmark of 2 acres per 1000 residents (CPD 2016). Many of these plans also involved community workshops, such as CMAP’s Pilsen and Little Village Land Use Plan, which revealed a desire for the Sangamon Paseo to be developed along with further bike and pedestrian infrastructure including river access points and connections to Western Avenue.

The mass mobilization of government and private resources surrounding El Paseo and Pilsen illustrates the intense interest that developers have had in the neighborhood. Over the 17 years since the first Quality of Life plan was introduced, gentrification has intensified in Pilsen while developer’s interest surrounding El Paseo has grown. This pressure is felt by Pilsen residents and with people involved in the garden, who often voice their concerns over displacement, and has contributed to community organizing surrounding affordable housing.

Pilsen Alliance: Sustainable Policy

Affordable housing is “putting bandaids on bullet wounds.”

– Javiar Ruiz, Pilsen Alliance

The Pilsen Alliance is a social justice organization that is working to combat gentrification within Pilsen through a combination of community outreach and policy advocacy. They strive to create sustainable policies so green spaces can be a right and not a cause for gentrification. Javiar Ruiz, a member of the Pilsen Alliance, discusses policies the Pilsen Alliance advocates for. He believes these policies will put an end to gentrification, rather than treat the symptoms.

Legalizing Rent Control:

Rent control is currently illegal in the State of Illinois. The Pilsen Alliance believes legalizing rent control will have a large impact on combating gentrification. They have worked to push legislators, educate the community, and conduct public polling on the topic of rent control. In 2018, they conducted a community referendum and found that 70% of the Pilsen community was in support of rent control.

Just Ordinance Cause:

The Pilsen Alliance is fighting for the City of Chicago to put a policy in place that will force landlords to give a just cause to evict. Right now, landlords can evict tenants without any justification. A Just Cause Ordinance would offer some protections to tenants.

Healthy Homes Ordinance:

The City of Chicago has a set of standards landlords must abide by for maintaining the conditions of their properties. Small landlords are often penalized by these policies and are forced to sell their homes. The Pilsen Alliance is proposing a system to provide grants to small landlords for general repairs and maintenance.

Social Housing Pilot:

The Pilsen Alliance is also drafting a policy for a Social Housing Pilot. This program would be a better alternative to affordable housing. In this model, housing would be shielded from the forces of the market. Renters would always pay 30% of their income, regardless of how market prices fluctuate.

Connecting to the Garden

21st Street Between Peoria and Morgan, Image from Imgur, Fifty Changes in Pilsen over Fifteen Years.

The rise in gentrification in Pilsen has coincided with the formation and growth of El Paseo community garden. Many garden-goers are community members, but they have also felt the impacts of gentrification on the garden directly. Miguel Del Toral, a lifelong Pilsen resident, worries that Rahm Emanuel’s El Paseo trail–independent from El Paseo garden–is a “tourist attraction.” Though the garden makes it clear that it is welcome for all, as stated, members of the garden are contending with many of the harms and impacts of gentrification, leading to tensions between who the garden should be for and who is benefitting from its programming.

Tweet from @Vickofor15, Victoria “Vicko” Alvarez, April 20, 2023.

Another longtime garden participant and Chicago resident of 41 years, Daisy Morales, has been forced to relocate within Pilsen and Little Village multiple times due to rising housing costs. Most recently in January of this year, the building that Morales rents in was bought by a developer who hopes to remodel and raise rent by as much as three times what Morales pays currently. In an interview with Morales, she expressed her frustration with affordable housing in the neighborhood stating that “still low income homes are not low income because I didn’t qualify for a low income apartment, because a studio was, they had a studio available for me, for almost $1100… So even with low income housing, it’s really high for people like me.” But Morales notes that the garden, despite the changing demographics of the neighborhood, is still a vital community space for all. “You can see the changes in the garden too but, then again, I honestly see a beautiful mix at the garden.”

We also spoke with Paula Acevedo, the co-director of El Paseo community garden, about her experiences with gentrification and its effect on the garden. Acevedo expressed frustration with developers and the commodification of the garden, and said “our hard work and labor and efforts that are meant for community are being exploited for profit, essentially…[I] have seen posts where it’s the views of the inside of the house and you’re swiping, and then it was a picture of the garden.” Acevedo also emphasized the garden’s relationship with nearby affordable housing, stating that their presence is “supposed to kind of mitigate those effects…However, even the definition of affordable is not accessible and so people are even being displaced from the quote unquote affordable housing. And so we are losing families and seniors that have been living in those buildings since they were built in 2009.” Acevedo struggles between feeling proud of her work and worrying that it is being co-opted for gentrification. She said, “I think that everybody does appreciate [the garden] and has respect for the work that we do, and so that really makes me happy…[because] we’re not the cause of the gentrification, right? It’s this larger system. It is a nice amenity, but it’s the exploitation of community. People who, who make the community better, who fought for the coal plant to shut down and who fought for the school, who fought for the library. Like it’s exploitation of everybody who’s poured their heart into the community to make it what it is really.”

Tweet from @kdjzuz, October 5, 2020.

During our conversation with Acevedo, she brought up a very recent and tragic example of gentrification affecting the community at the garden. A senior couple, who had lived in the affordable housing apartments by the garden since 2009, and been involved with the garden throughout that time, recently got displaced from their housing. According to Paula, they did not have Section 8 housing, and consequently their “affordable housing” got too expensive for them to stay in the neighborhood, leading to their move to a distant Chicago neighborhood. However, “not even a month in, he [the man in the couple] passed away. He was 89 years old and he passed away…And so you kind of think you’re not supposed to move seniors. That’s not good for their health.” It is clear how gentrification uproots community members and the impact that losing their community, context, environment, and resources can have on their health. Acevedo expressed her deep anger in this case, stating rhetorically, “you can’t do more to protect the people in the community? Like you cannot find some kind of way to subsidize.”

“So I’m mad, but like I said, the seniors, they’ve been through it and it’s just the way it is and they don’t hold on. They’re just like, yeah. We were displaced when UIC was built, when the highways were built, and this and that…It wears people down. People are too busy trying to survive and figure out where they’re gonna live than how they’re gonna, you know, do anything to fight for their rights to speak up or to have the capacity to speak up. And so that’s the classic. Keep communities divided, keep people disinvested and the rich will be rich and the poor will be poor. And that’s just capitalism, honestly.”

– Paula Acevedo, El Paseo Garden

Conclusion: Quedarse En Pilsen

Gentrification is an ongoing problem, but it is one that can be eradicated through policy measures that prioritize community members and strive to serve people over profit. Residents should not be fearful of being priced out of their homes, and volunteers and gardeners at El Paseo should not be fearful that their hard work is going to be exploited to further push the agendas of gentrifiers and developers. Developers, profit, and capitalism should not be the controllers of our neighborhoods and destroyers of communities. Policymakers and city leaders must include community members’ in the decisions that shape their neighborhoods and housing. We should look toward the mission of the Pilsen Housing Cooperative: quedarse en Pilsen, or, to stay in Pilsen.

Sources:

- https://interactive.wttw.com/my-neighborhood/pilsen/gentrification

- https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/126764/Lower+West+Side.pdf

- https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/chicagocityillinois/PST045222

- https://www.zillow.com/home-values/33420/pilsen-chicago-il/

- https://www.point2homes.com/US/Neighborhood/IL/Chicago/Pilsen-Demographics.html

- https://www.housingstudies.org/data-portal/geography/lower-west-side/

- https://voorheescenter.red.uic.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/122/2017/10/2005-Gentrification-before-gentrification.pdf

- https://chicagohealthatlas.org/neighborhood/1714000-31?place=lower-west-side

- https://elpaseotrail.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/betancur_study.pdf

- https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/doh/provdrs/developers/svcs/aro.html

- https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/BillStatus.asp?DocTypeID=HB&DocNum=2430&GAID=14&SessionID=91&LegID=103158

- https://ilga.gov/legislation/BillStatus.asp?GA=101&SessionID=108&DocTypeID=HB&DocNum=255

- https://www.huduser.gov/portal/rbc/search.html?DocID=3268

- https://www.huduser.gov/portal/rbc/search.html?DocID=3269

- https://www.huduser.gov/portal/rbc/search.html?DocID=3267

- https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/doh/provdrs/developers/news/2021/march/city-council-passes-606-pilsen-permit-surcharge-ordinance.html

- https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/doh/provdrs/housing_resources/news/2020/december/mayor-lightfoot-and-department-of-housing-introduces-ant–deconv.html

- https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs3.asp?ActID=748&ChapterID=11

- https://ilga.gov/legislation/BillStatus.asp?DocNum=2192&GAID=15&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=117947&SessionID=108&SpecSess=&Session=&GA=101

- https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/dcd/provdrs/ec_dev/news/2022/february/city-acquisition-of-pilsen-site-will-ensure-its-redevelopment-fo.html

- https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/mayor/press_room/press_releases/2016/march/Mayor_Emanuel_Announces_Paseo.html

- https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/dcd/provdrs/sustain/news/2020/september/land-sale-would-support-expansion-of-el-paseo-community-garden-i.html

- https://www.huduser.gov/portal/rbc/indepth/interior-022822.html

- https://displacement-risk.housingstudies.org/

- https://www.chicagocityscape.com/address.php?address=944%20W%2021st%20Street&city=Chicago&state=IL&zipcode=&county=Cook%20County&lat=41.854206&lng=-87.649855

- https://www.dnainfo.com/chicago/20160510/pilsen/solis-moves-block-development-of-massive-pilsen-site/

- https://www.dnainfo.com/chicago/20161118/pilsen/paseo-trail-little-village-606-bloomingdale-bnsf-railroad-tracks-train/

- https://www.proquest.com/docview/2673069875/8C9B4190D9EB45F8PQ/3

Plans:

- https://www.dropbox.com/s/21ouhliu5jejij7/Land%20Acquisition%20Plan%20DOD%209.pdf?dl=0

- https://elpaseotrail.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/pilsen_qofl_2006.pdf

- https://elpaseotrail.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/2015_pilsen_lv_landuse_dpd_cmap.pdf

- https://elpaseotrail.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/final-pilsen-qol-plan-full.pdf

Connecting to the Garden:

Images, Videos, Tweets:

- https://akitotsuda.wixsite.com/akitotsuda/pilsen-days

- https://imgur.com/a/FGQ1qPm

- https://rogershermanhouse.com/2020/07/03/pilsen-a-blending-of-czech-and-mexican-american-communities-by-the-neighborhood-service-association-of-chicago/

- https://tamaleria.wordpress.com/pilsen-history/pilsen-in-the-1990s/

- https://twitter.com/VickoFor15/status/1649183455635177472?s=20

- https://twitter.com/kdjzuz/status/1645170922301665283?s=20

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI71JXxzEoU