Opioid Use Disorder, COVID-19, and Telehealth

2020 was undoubtedly a devastating and unprecedented year. People experienced an inversion of their lives, death of family and friends, and other COVID-19 related upheavals. However, for some individuals, COVID-19 was not the only public health crisis they were facing– the stresses of the pandemic came with a resurgence in the Opioid Crisis in Chicago. However, since everything was in lockdown, the form of treatment had to change and we need to understand how everything played out for the communities, patients, and providers testing out telehealth for the first time and trying to help those struggling with OUD.

Our research questions were:

- How did community-based clinics respond to substance/opioid-related needs & what was the experience of providers/patients?

- What role does telehealth play in community & clinical response to the Opioid Crisis within Chicago neighborhoods?

We sought out and reached out to various clinics that offered either various inpatient or outpatient services for OUD in Chicago, allowing them to opt-in if they were interested in participating. This study consisted of semi-structured interviews with various clinic program administrators, social workers, and health care providers in Chicago, primarily in the West side. All interviews were recorded with consent, transcribed, and deleted at the end. Any identifying information about the interviewees or clinics were removed from the transcripts for the sake of protecting participant confidentiality. Finally, we analyzed the transcripts to look for common themes and experiences.

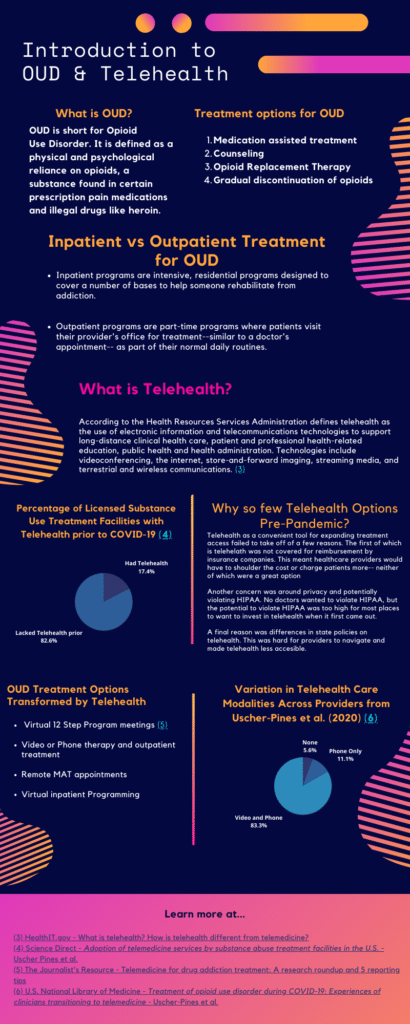

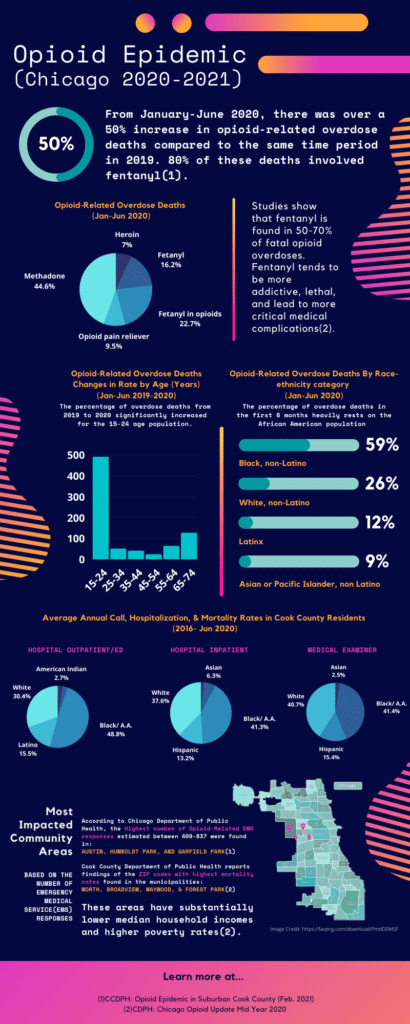

The infographic above presents a compilation of the most recent statistical data presented by the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) and Cook County Department of Public Health (CCDPH). It is a critical reference to the following interview article we have developed thanks to the conversations we had with various stakeholders battling against OUD and substance abuse in community-based clinics located primarily on the West side of Chicago. The highlighted quotes and major themes of this narration express personal experiences and beliefs of those interviewed. Their personal and professional identifiers are kept confidential to ensure an open environment for them to speak upon their workspace experience, or their own patients’ experiences with telehealth, the recent COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the opioids and the opioid epidemic. We would like to thank them for their time and great insight.

On the Opioid Epidemic:

The CCPH’s statistics Mid Year 2020 Report on Chicago Opioids highlighted a surge in two particular age demographics that have been most affected in the past year compared to 2019. This finding, according to the program manager of one of Chicago’s mental and substance disorder centers, does not add up to what they are currently observing in patients who are receiving treatment and they believe that there are possible barriers specific for these two groups to receive treatment. “Where 15 to 24, that’s high school — college age, those individuals are not thinking about treatment or therapy. Those individuals need an advocate, they need a parent or guardian or a system–whether it’s court or school— or something of the kind making them get into treatment or consenting for them to do treatment. And then we know there’s always been barriers for the elderly population…we see higher rates of a lot of stuff, whether it’s substance use or sexual diseases…where we don’t really pay attention to that population at all”

But exactly what is causing this increase of overdose deaths? And does the pandemic play a role in the surge at all? The medication-assisted care coordinator shared with us that they have seen a spike of fentanyl in patients’ urine drug screenings which clearly supports the report highlighting an increase in fentanyl involved in opioid overdoses. All of our interviewees pointed out how fentanyl is more addictive and deadlier than opioids, but also how it has also become potentially easier to acquire in the country during the early stages of the pandemic. “A lot of it is because the fentanyl that’s available in the streets being cut with almost every drug that exists, now it’s in marijuana, it’s in opioids, it’s in cocaine, it’s in everything. And so the people who are using to escape all of those harsh realities that are worsening by the pandemic are dying.” Some presented us with a second theory for the differences in overdose deaths across age groups grounded in the lack of bodily capabilities in both younger and elder groups to endure the new potency of fentanyl, a more deadly substance contained in their substance intake. Now, Chicago’s West and South side communities must not only struggle with the recent COVID-19 pandemic, but additional deaths due to the consecutive opioid epidemic.

Outreach’s Role Now and Before:

Before the pandemic many of these communities, according to the program manager, had already identified mental health and substance use counseling as some of their greatest needs, but regardless they point to how “It’s one thing to recognize that there is a need in the neighborhood, and a different thing to get those people who may need it into treatment”. Here’s where outreach becomes crucial in these particular communities. One obstacle in outreach they all pointed to is the lack of knowledge of the existence of clinics like theirs. Some people do not know of mental and substance use services available to them even if a community has been able to proactively both vote in request of such services and agree to contribute through their tax bills in order for services to be kept at no-cost. Methods used to advertise the resources available to them currently use combined multimedia formats that include but are not limited to radio PSA’s, television commercials, physical mailings, churches, and social media blasts specifically created for particular times and days to further reach their targeted audience.

The outreach coordinator shares a crucial question that is often asked and attempted to answer even more now due to the consequences of the pandemic: “How do we reach people who are in active addiction? And kind of the big thing is that we’re not selling cars here, we’re talking about treatment. So someone who hears that message might not be ready to receive treatment yet. But hopefully it plants a seed, even if they’re in the middle of addiction that might grow later” Here they are hinting towards a need for a more personal and understanding approach that is specific to the needs and comfort of the individual who will benefit from receiving treatment. For example, an obstacle in reaching people of color is overcoming their skepticism of receiving help from mental health providers, especially from the black community. So oftentimes outreach through either a friend or family member that they trust referring them to the right direction can become more successful and fruitful in the long run to battle even the additional stigma that still remains in these communities (more on this particular topic further down). While the virtual platforms increased the efficiency of outreach by saving time and increasing the reach that drop offs or pop ups were limited to, it also raised skepticism and added an extra layer of trauma in other cases. Most clinics require extensive and sensitive information to be provided before admittance into either an outpatient or inpatient treatment clinic, but when the potential client is requested this upon a call or email and have not met someone or seen the building in-person they feel understandably reluctant to share.

For an individual who suffers from substance use, it can be very difficult to ask for help in the midst of their addiction, so the window when they want to change and receive help can last very short times and thus the medication-assisted care coordinator emphasizes the need to also find ways for clinics to be easily reachable at any time. “I want to be as accessible to individuals with substance use disorders as their dealer. Why is it harder for them to access treatment than their dealer is in order to access their substances?” A personal solution they have actively incorporated into their profession is their willingness to provide anyone–either families, other clinics, and local organizations– their own work number. They have noted that direct contact has a crucial role in outreach because oftentimes an individual who is left on hold or has no one picking up their call for help may lead them to feel uncomfortable to ask for help ever again.

Obstacles During the Treatment Process

Regardless of the pandemic, all interviewed pointed out some way or another that stigma remains a critical factor to overcome in outreach and during the treatment process. Especially when the most impacted areas of Chicago are predominantly composed of people of color who have historically and now stigmatize treatment for substance use health. “Stigma surrounding addiction and getting treatment is still alive and well. And that’s something that we do battle with some of the outreach, like stuff that I do, is to end that stigma. And to let people know it is a huge barrier, because people don’t want to be perceived as weak, or they don’t want to be perceived as lacking willpower. They don’t want to be perceived as an addict, or an alcoholic, or whatever that idea of it is. So that’s a huge barrier that people do describe when they come into treatment.” Another obstacle in the treatment process that has only been exacerbated, but existed before the pandemic, is the West and South side environment that the patients are in. In these areas drugs are more accessible, making the environment very difficult for patients to navigate during and after treatment, and with unemployment high due to the pandemic some are left with no choice but to sell drugs to maintain themselves or their families.

The pandemic’s necessary social distancing negatively impacted the heart, if not a crucial aspect, of all kinds of substance treatment plans: “Often the opposite of addiction is connection. And people really want that continued connection and to live with others who are struggling with what they’re struggling with”. Outpatient and Inpatient treatment programs are crafted with many social components to keep the patient engaged, busy, and ready to integrate themselves to their communities. With services already sparse, the pandemic caused the number of people participating in counseling limited and at the greatest rise of cases cancelled for months. Some outpatient agencies have not been able to continue contracts with inpatient facilities to send out patients for intensive outpatient care limiting the number of opportunities available for patients to socialize and cause some setbacks in their recovery, “Some of the [patients] have co-occurring diagnoses and so being isolated, in their home for days, weeks at a time, and trying not to drink or get high was nearly impossible. Because, you know, when leading up to the pandemic, I’m making a list of coping skills, distraction, things you can do, and then suddenly, all of those possibilities are taken away.” In the case of medical-assisted programs, the social component is even more crucial to decrease the chances of overdose deaths by having patients use substances in company of others, and the pandemic doesn’t help enhance this, which could be an additional explanation for the increase of overdose deaths in the past year.

Changes & Adjustments to be made moving forward

Some of the hopes that they have moving forward is the understanding of policymakers and the general public alike on the importance of treatment, “And I’m hoping that the thing that people learn from it is that mental health services are important. So I see that from multiple different standpoints, whether that’s realizing, okay, well, this last year sucked real bad. And I need to actually, like, take care of myself. And now on a much larger scale, more funding for mental health services, widespread… there is still a great need for mental health services throughout Chicago, throughout the country.” But even more importantly they hope more preventative measures are placed instead of the need for crisis interventions like the Opioid Epidemic Chicago has faced recently.

As far as outreach, one of the interviewees mentioned working on a solution to hopefully better serve the patients on their first point of contact with having agencies update their direct contact for appointments in order to be part of his platform, “One thing I’ve been working on is a Google Map. My hope is that I’ve been inviting different care coordinators at different agencies. Because otherwise a big frustration even for care coordinators is trying to get that individual that can actually set the appointment up versus calling the front desk and the front desk individuals not knowing what the heck we’re going to do. One beautiful aspect with that is I can place in like where are patients located or where their home address is and see which clinic is closed by, figure out what services they offer, and if it matches what the patient needs.”

And last but not least, virtual platforms have effectively provided patients with greater accessibility to treatment by being reached at their place and time of convenience for them to still be able to continue their own responsibilities, in the case of parents they would not have to worry about childcare for example. But there still remains a thin line that providers will continue to tackle now and post pandemic: being accessible while integrating responsibility in the treatment process when patients had to go to treatment in person, “part of my appreciation for [in-person treatment] was it sort of teaches your clients as they’re working on things, okay, I need to be responsible and accountable in this way. And then sort of hoping that at the same time, they can generalize it to other areas of their life.”

Healthcare at a Distance- Telehealth

This past has been a year called for drastic change in how we all lived our lives and the field of medicine has had to try a new model of care: telehealth. We could return to non-utilization of telehealth, but we have stepped towards the future of health care, and perhaps it would be wrong to ever step back.

From the interviews with the various clinics, it is clear that telehealth has had a major role in continuing care in these extraneous times. Certain themes have come in the interviews that tell the story of what role telehealth played in community and clinical response to the opioid crisis within Chicago neighborhoods.

A Quick and Tough Transition– Clinic Resilience

A majority of the clinics we interviewed did not have telehealth prior to the pandemic, with one having just gotten telehealth instituted, but not necessarily refined. The sudden plunge into the pandemic and new lockdown protocols sent many workplaces in a mad scramble to reorganize, but the challenge for clinics was unique. None of them had any guidance or public authority to follow as they were left to figure out telehealth and remote clinical work. As one interviewee put it, “ We were just thrown into the fire.”

Because of the lack of guidance, each organization had to test a variety of platforms in a trial-and-error fashion to carry out visits or remote programming. They had to ask themselves, “What is the best way to conduct a remote visit? What computers, cameras, microphones do we need in order to create the most engaging and smooth remote session? How can we schedule and send out appointments best to our patients?”. The learning curve inpatient programs and outpatient programs differed slightly as inpatient programs relied on telehealth for specific programming that could not otherwise be offered in lockdown. In compliance with COVID-19 regulations, the inpatient programs did their best to offer as much in-person interaction as possible. Outpatient programs relied more heavily on telehealth, given that their patients were not physically located onsite and the nature of outpatient treatment differs. As such, the technical learning curves for these programs were higher as they had to take extra considerations for billing and outreach.

However, despite the confusion and stress of testing out various platforms, technologies, and methodologies, a consistent sentiment came from all of the clinics: resilience. Each clinic was proud of their ability to make a quick pivot into telehealth, especially given that they did it on their own. Naturally, this was a bigger challenge for smaller organizations who had to find grants or funding to acquire tools to smooth their transition, but in the end they were able to do so. In some cases, certain platforms not designed with the medical field in mind surprisingly were the very tools clinics found useful in operating remotely.

“I kind of wish that there was more guidelines at first, but no one had any guidelines. So we were kind of all figuring it out together. But it really worked out and our team is fantastic and really acclimated quickly to providing telehealth.”

Concerns in Maintaining Patient Confidentiality (HIPAA), Privacy, and Trust

One of the largest hurdles in adopting telehealth was navigating patient confidentiality and privacy. As a provider under HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, providers must protect patient’s sensitive health data. Prior to the pandemic, the clinics said that one of the reasons they never utilized telehealth before was due to fear of violating HIPAA. This continued to be a source of concern for clinics at the onset of the pandemic and a couple clinics reported being hesitant to fully embrace telehealth until it had been announced that telehealth was not a HIPAA violation.

Trust is a major part of any patient-provider relationship and it dictates the ability of a provider and patient to resolve the health issue. Naturally, with a topic as sensitive as opioid use disorder and the introduction of telehealth, trust was something clinics found themselves having to build. One clinic mentioned that at the beginning, their patients were uneasy because they had a harder time discerning what was a scam and what was their actual provider. A consistent experience across the clinics was that patients would have their cameras off, take a little longer to open up, and generally had a distrust over the safety of their private session. In group therapy sessions, some patients feared being recorded by someone else as normally in person they could see each other and share their stories, but know nothing else about the other people. Relationship building with new patients was also a challenge for some of the clinics as some patients would question their legitimacy and it was hard for them to match up the idea of a physical clinic and the providers they were speaking to, especially when video calling was not an option.Furthermore, not all patients had a safe and private space to themselves for them to open, as one of the providers mentioned that many of their clients did not want others to know they were seeking help.

On the flip side, some patients were overly comfortable doing their telehealth appointments in a variety of places, including the grocery store, in family common spaces, and in front of friends. From a HIPAA privacy standpoint, conducting the appointment in these non-private settings sound concerning, but as long as the patients consented and felt comfortable, the green light was there. One provider even reported that a young client was incredibly vocal about seeing a therapist in front of their friends. The provider mentioned that it would feel odd to be pointed out in public as someone therapist, but attributes this new openness to the idea of seeing a therapist as a trend among youths.

Telehealth and lowering barrier thresholds to care

Overall, the clinics reported that providers and patients had generally had a positive opinion and experience with telehealth, citing convenience and surprising success. The clinics all reported either no increase in appointment no-shows, a decrease in no-show appointments, or saw new and more engagement as a result of telehealth. For providers, telehealth was an advantageous tool that was convenient, especially if the clinic had outside partners they collaborated with. It removed the need for any travelling cost for the clinics and their partners, was easy to arrange appointments with patients, and generally provided more flexibility. In some cases, clinics were able to easily follow up on patients who were late or did not appear for their telehealth appointments using a phone call. This avoided the extra hassle of needing to completely reschedule patients. Clinics that offered medication assisted treatment also mentioned how the easing of requirements for prescribing buprenorphine or other medications to patients made visits and prescribing easier for both parties. For some patients, monthly visits to be cleared to receive another prescription was not feasible or drastically interfered with their work schedules. However, with telehealth being greenlit for prescribing medication, many of these issues then disappeared and opened up access to care for many patients.

Patients had a generally positive experience with telehealth as it cut down their transportation costs and saved them time. It also provided the flexibility to take the appointment anywhere or watch after their kids if needed. However some patients expressed to their providers that they still preferred in-person treatment; they felt that it was harder to get the same level of care through telehealth. A couple providers also shared this sentiment as they noted that telehealth prevented them from seeing their patient in whole and reading body language or other cues that would help them work with the patient. This perhaps is unavoidable, given that phone calls have no visual component and video only shows certain portions of the patient.

In general, the clinics we interviewed had positive things to say about telehealth and were excited that it had opened up accessibility of treatment for many people. As one provider said, “…we talked about low threshold treatment is what we’re aiming for, and that telehealth allows for that.”. By low threshold, the interviewee was referring to removing barriers to treatment such as transportation costs, schedule issues, and regulations which keep patients from easily getting help when they want it. As the clinicians said, it is hard to help someone who does not want to change or receive help, and catching them in that ephemeral moment when they do can be hard. One interviewee said, “ I want to be as accessible to individuals with substance use disorders as their dealer. Why make it harder for them to access treatment than their dealer is in order to access their substances?” Afterall, many of the patients that these clinics work with live in neighborhoods where drugs are pervasive and easily accessible. A few providers mentioned the worry that their patients would easily relapse or continuously struggle because a dealer was only an immediate or few connections away.

“I want to be as accessible to individuals with substance use disorders as their dealer. Why make it harder for them to access treatment than their dealer is in order to access their substances?”

The Digital Divide

Telehealth is wonderful tool that expands treatment access, but its success lies on the

assumption that all people have a device and some access to wifi. This is not always the case as there is inequitable access to technology. As many of the interviewees agreed upon, maintaining the same quality of care patients would receive in-person during a telehealth visit can be difficult, and even more so when patients can only do phone call appointments. There are certain cues which help providers read their patients, such as pupil dilation or fidgeting, which do not come through in telehealth. In an effort to address part of the equity issue, one clinic sought out grants to provide laptops for some of their patients so that they could continue treatment. Of course, it is difficult to know the true scale of need and appropriate response to help all patients have access to some device and it is questionable if it will ever be known how many people were lost in the cracks during the pandemic.

Even between clinics, there was a difference in the level of technologies available to them or that were familiar or easy to use for their operations. Sometimes this boiled down to a funding issue or general unfamiliarity with telehealth technology that had to be overcome. Wifi even interfered with some providers’ sessions, whether it was on their ends or the patients’

Thinking Ahead: Recommendations for the Future

After a year using telehealth, many of the clinics said that they would most likely continue using it as part of their programs. They all said that they would like the COVID-19 emergency authorizations on telehealth provisions to become permanent so that telehealth continues to be easy and accessible. In particular, clinics which offer medication assisted treatment wanted telehealth appointments to continue being permitted for prescribing as they felt this drastically helped many patients avoid an otherwise time-consuming and disruptive monthly appointment. Especially in the cases where it is a simple check-in and renewed prescription for buprenorphine, providers felt that it was unnecessary to follow the old requirements.

“So, you know, we all want to play, you know, by whatever the rules are, but we want to make sure that we are making treatment as accessible as possible to patients”

In order to continue telehealth as an accessible route to treatment, clinics said that grants or funding, especially for small community clinics in minority neighborhoods, would be needed. After all, no money, no mission. More broadly, providers hoped that the fair compensation for telehealth would also be key to telehealth longevity; prior to the pandemic, it was unclear and even not guaranteed that a provider would be compensated for telehealth and these services would have to come out of the provider’s pocket. In the long run, this would not be feasible for the clinics, so if we hope to keep telehealth, billing and compensation policies must be standardized and fair to providers.

In addressing the digital divide, something one of the providers mentioned was wifi as a basic right for all. This would then allow more people to do telehealth appointments for OUD, but also help address other issues, such as searching for gainful employment, which have important implications for overall patient stability and recovery. City-wide free wifi may take a long time to reach, but the creation of private spaces with computers with cameras and free wifi could help address the digital divide providers saw with their OUD patients.

Finally, more research into the best telehealth practices would be of significant help to the clinics as most of them felt that they were scrambling to figure out telehealth on their own. This research could then create a standard for telehealth best-practice and education for clinics and even patients. As some interviewees said, it was hard to determine what constitutes an effective, worthwhile visit for the patients and the way to achieve that. Moving past this year of experimentation, there must be something that can be learned and refined into an “evolving” best-practice.

Reflection

It is exciting to think that we are at the beginning of a new era of treatment, though the transition to it was unexpected and during difficult times. The clinics we spoke to are but a handful of others who may have had similar or even different experiences. We are incredibly fortunate and thankful that we were able to hear and share their experiences and lessons learned, and we stress the importance of reflecting and speaking to the people at the forefront of this transition so we can all prepare for a better tomorrow.