Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Asian-American Chicagoans Confront COVID-19

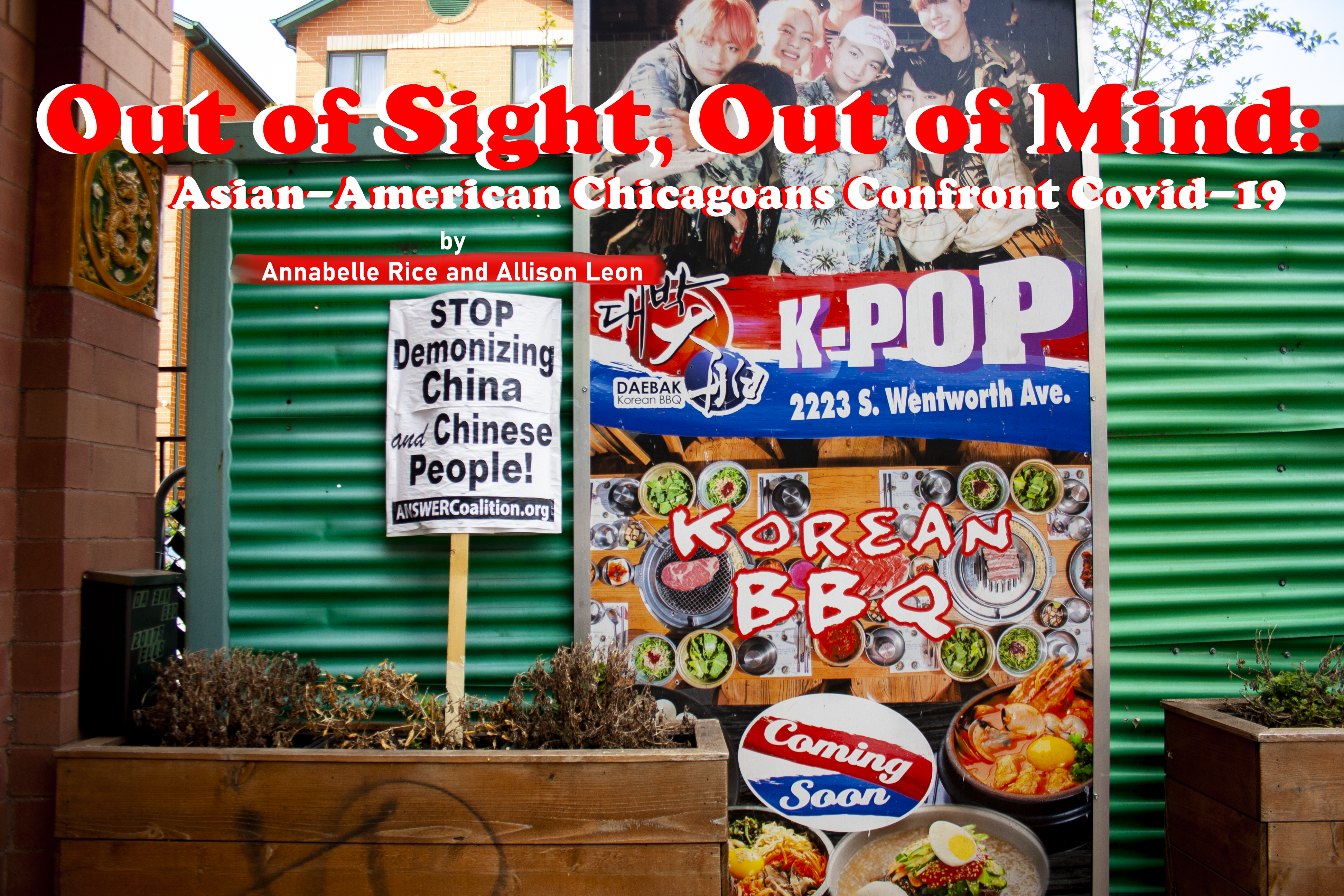

#StopAsianHate: a hashtag that I have watched decline in popularity on my social media feeds as quickly as it ascended. An explosion of social outcry was inevitable this year: a 150% increase in Anti-Asian hate crimes in 2020 regenerated at an exponential pace in 2021. Attacks on Asian citizens ranging from mass murder in Atlanta to box cutter slashings in the Manhattan subway, and the 4,000 reported incidents and counting revealed an unsettling tide of Anti-Asian aggression across the country, exacerbated by the “China virus” and “Kung Flu” rhetoric of Donald Trump’s presidency. After Trump first tweeted #chinesevirus in March of 2020, University of Southern California researchers found that the number of people using the hashtag increased more than tenfold within one week and its inclusion was highly correlated with Anti-Asian language in other tweets. A year later, the mass murder in March 2021 of eight Atlanta massage parlor employees, six of whom were Asian women, revealed that emboldened Americans were more willing than ever to turn hate speech into hate crimes.

And yet, by mid-April, #StopAsianHate appeared to have met the fate of countless other online activism campaigns that came before it. Mentions of Atlanta and the usual infographics on mental health resources and GoFundMe pages became few and far between on my feeds, disappearing almost entirely since. It seemed to me that #StopAsianHate had merely been discarded once its social media currency began to decline in value, leaving Asian-Americans once again in an all-too-familiar position: silenced.

The terror and anguish that has swept through Asian communities across the country is very real. I felt it, my roommate felt it. People who look like my Filipino mom and her Korean dad are being harassed, assaulted, killed, and blamed for the existence of a virus that emerged thousands of miles away from them. For most, exposure to the plight of Asian-Americans was limited to the online half-life of a hashtag. But over the months since Atlanta, I realized that this new dimension of consciousness and concern for the safety of my family, of the Asian population, is here to stay.

By the start of this spring quarter, attacks on Asians had mounted in number and severity exponentially on both coasts. Our Mapping Global Chicago lab began and I recognized that this was a chance to join the movement against Asian hate in a way that extended my activism beyond the realm of Instagram and Twitter. This project’s goal was to shed light on the experiences of Asian-American Chicagoans during the pandemic and amplify the voice of a demographic now more at risk of hate-driven violence than ever.

I interviewed five Asian-American residents of the Chinatown, Bridgeport, and Uptown neighborhoods. It wasn’t easy getting in touch with locals during the pandemic, and I found my interviewees through a combination of social media and email outreach, snowball sampling, and approaching them in Chinatown with the help of Cantonese and Mandarin interpreters.

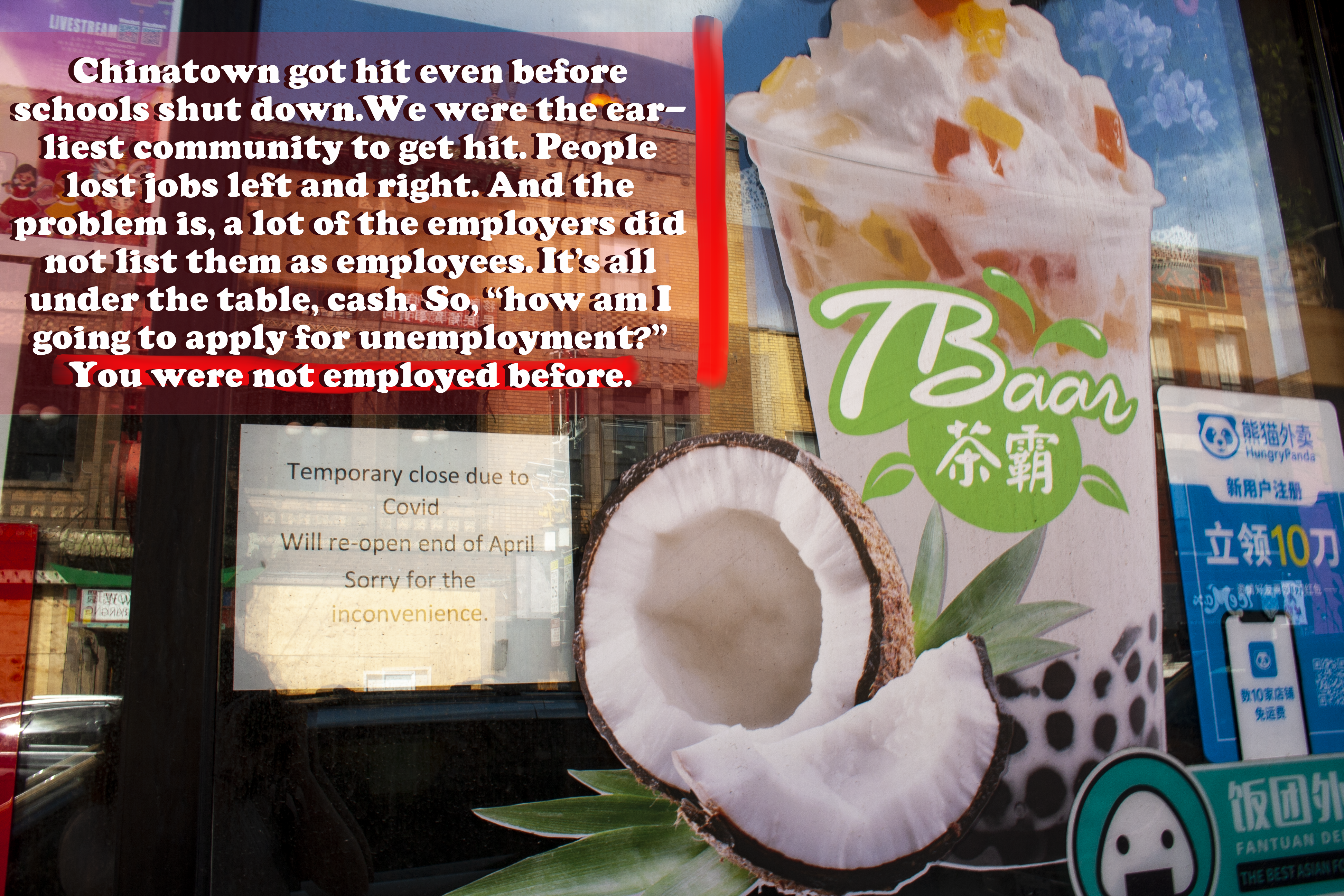

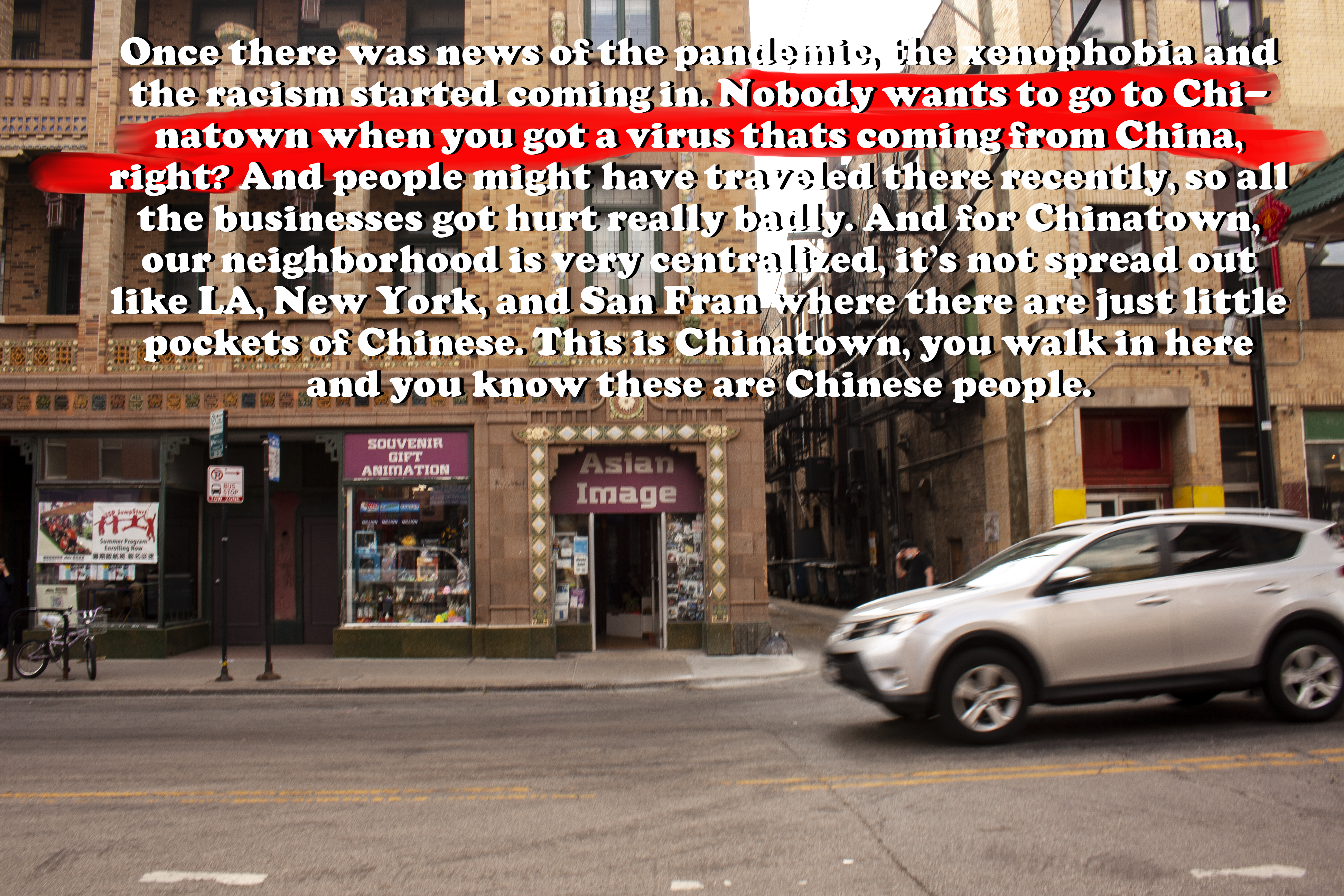

Chinatown began to suffer from the pandemic first and hardest of Chicago’s seventy-seven neighborhoods. “The xenophobia and the racism started coming in and people just didn’t know [anything] about [the virus.] Nobody wants to go to Chinatown when you got a virus that’s coming from China, right?” says Chris Javier, a deacon at the Chinatown Christian Union Church. Bonnie Ho, principal of the Pui Tak Christian School on 23rd and Wentworth, told me that people lost jobs much earlier on than in other communities, and because most employment in Chinatown is under-the-table, those that were out of work could not even file for unemployment. The neighborhood’s restaurant-driven economy nosedived, demand for hair salons and spas ran dry – and first-generation, often non-English-speaking workers lacked the means to find employment elsewhere.

On March 26th, a Vietnamese man was punched in the head and stalked by another man with a baseball bat while on a walk in the Asia-on-Argyle neighborhood, just blocks from his Uptown home. One month ago, a man drove a truck into a picnicking group while yelling anti-Asian slurs, severely injuring a 43-year-old woman. These aside, The Chicago Sun-Times reported that the number of racially-motivated crimes against Asians in Chicago “remains low,” potentially as a result of traditional resistance to seeking law enforcement intervention for incidents of racism or harassment. “For us as Asian-Americans culturally, we were raised to not ruffle any feathers and just mind our own business. It was tough to get our community to say their piece about it,” said Derrick Apigo, an Uptown resident with family in the Chicago suburbs. “I think we realized they needed a more intimate space rather than putting them on a huge platform to talk about what’s going on and condemn it.” I learned from Chris that the lack of reporting can also be for spiritual reasons: “Don’t talk about it, that’s a very Chinese-Confucian thing. Don’t talk about evil, don’t talk about bad, because it brings it about more. And so, they internalize and store it up, and that can have generational effects.”

I suspected there was more to these purportedly low rates of Anti-Asian violence than met the eye. I spoke with Julie Malaga, a Bridgeport resident who confirmed that below a surface-level statistic – only two hate crimes were recorded by the CPD in 2020 – lay a story much more telling of the dilemma facing Chinatown. “I would agree that it’s underreported. Because – and that predates the pandemic – it’s because they don’t trust the cops,” she said of the neighborhood. “A lot of them don’t have papers, especially in Chinatown. So they just don’t want to get involved. I’m sure it’s happening a lot. That’s what my aunt said. There’s a WeChat that reports all these things that are happening in Chinatown. The police think there’s no problem there because it’s not in the numbers.”

Chicago’s Chinatown is a highly insular community: its first-generation immigrant population generally remain in the same profession for years after their arrival, it’s difficult to communicate with locals unless you’re fluent in Cantonese, and crimes are often shared in a WeChat rather than with police. On top of this, it’s rare for Chinatown residents to commit crimes within Chinatown itself – the majority are traced to those from its adjacent neighborhoods and beyond, said Chris. “In February of 2020, there was a double murder. And that rocked our community, because there isn’t much violent crime within our community perpetrated by our community. It’s people from other communities coming into ours and committing crimes.”

The Pui Tak Christian School, where Bonnie is principal, is the sister organization of the Chinese Christian Union Church. Pui Tak was broken into twice this summer, the second crime committed just one month after the first. “My personal belongings were gone. The police couldn’t give us an answer. For a period of time, I did not feel safe,” she said of the first incident. “I’m not sure if it ties into hate crime, but then a month later – [the second] was for sure a reaction of hatred.” Bonnie said that the act itself – a non-Asian man caught on camera throwing a brick through the window of the school, with no intent to enter, just to damage – underscored its motivation. “These two things happened within a month. Our security is in God, but we are human, and we have emotion too.” Bonnie and her cohort of mostly female teachers no longer feel safe walking by themselves to their cars after work, and all staff members are now required to leave the building in groups by 5:30 PM.

The break-ins at Pui Tak are isolated accounts that evidence an irrefutable trend: crime has been on the rise in Chinatown, taking on a meteoric trajectory in recent months, especially carjackings. “I have Chinese friends who say not to be in Chinatown after 10. There’s more gunshots,” said Julie. “My neighbor was a baker. He bakes in the early morning. And I said, well I’ve never heard gunshots here. And he said yeah, because you’re sleeping. You don’t hear it.”

I learned from Chris that ruse scams specifically targeting elderly Chinatown residents have appeared at unprecedented frequencies in the community. Scammers disguise themselves as utility service workers entering on official business, gather the homeowners in the basement, and while distracted, a second scammer runs inside, robs the house, and leaves. “They don’t have IG, they’re not on social media, and a lot of them don’t pay attention to the news,” he said of the senior population. “So they don’t know there’s a wave of violence against people who look like them in a different part of the country, and they need to know that.”

The rise in crime has gone hand-in-hand with increased support for police patrols particularly within the Chinatown community. This opinion extends from Chicago to Asian enclaves around the U.S: Carl Chan, head of Oakland Chinatown’s Chamber of Commerce, told Vox that he’d asked “all of our seniors in Chinatown and basically all of our businesses: Do you want to see police in this community? So far, I haven’t heard anybody say no.”

“I know in the past, people would say that the police are useless and not doing anything, I don’t think that’s true. A lot of the police are working really hard, and we begin to pray for policemen,” said Bonnie. “I think we need to have a balanced view of law enforcement.”

Mark Florido, the Board Director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice Chicago and a resident of Uptown, introduced a different perspective. “I’d like to point very specifically here to Chicago – the cops don’t protect us, too. And they actually are pretty violent toward us, particularly as immigrants.” In 2014, owner Jianqing Klyzek filed a federal lawsuit against CPD officers who raided Copper Tan and Spa, alleging hate crimes in the form of racially-charged physical and verbal abuse. Klyzek was handcuffed, beaten repeatedly, and called racial slurs, along the lines of “we’ll put you in a box and ship you back to China.” “They’re not keeping us safe either,” says Mark. “We are still a foreign person to them. We’re already over-policed in our respective neighborhoods and we don’t feel safe, so there has to be something else we can do.”

“We want to love and support our police and hold them accountable with equal fervor,” Chris remarked. He founded the Chinatown Peace Project, a community initiative that partners with local offices such as the 25th Ward Alderman, Chinatown Neighborhood Watch, and Deering District Police Department to educate and protect the neighborhood’s most vulnerable. The team conducts regular safety walks, which involve door-to-door outreach to seniors in the community. CPD officers fluent in Cantonese and English accompany them. “What we’ve seen is when our community supports the police and cooperates and provides information to them, we help them help us. But it’s different in different communities. Knowing that reality, we have to be able to say that them helping us here does not make them immune to criticism and calls for justice when people who are dressed like them are committing crimes against people of a different color than us.”

Tensions have arisen between the black and Asian communities across the country, and Chicago has been no exception. “As much as we don’t want to talk about it, a lot of the reports are from African-Americans attacking Asian-Americans. How do you justify that? What we concluded was that there is just a lack of knowledge and education within each other’s community. If you knew that person better, would you act the same way?” said Derrick, who has organized roundtable discussions throughout the pandemic for his Asian coworkers and peers, often centering on their experiences with hate-driven violence and the role of law enforcement.

Chris, who organized the Asian-American Christians for Black Lives and Dignity last year, said that despite the calls for unity from activists within each community, “what I’m seeing in the social pages for each group, you just look through the comments and that’s not it. There is hatred towards Asians, and you look at the Asian pages and it’s given right back. From what I’ve seen, if you ask Chinatown- they’re not buying it. They’re not buying the unity that’s proposed or being talked about, because they’re not seeing it, they’re not experiencing it, and it’s not speaking to their reality.” However, he noted that the relationships between Chinatown, Bridgeport, and Bronzeville communities had strengthened since the march last June, and that his church will continue to emphasize solidarity to promote peace between the neighborhoods.

The residents of Chinatown that have experienced aggression or violence, according to Chris, are even less likely to pursue the resources available to victims than they are to report the crime itself. “If you look for Asian-American counselors in this area, there are few that are Asian and have some language, but there are almost none that are Cantonese. Why is that? Because the people who speak Cantonese from Hong Kong, old school, there’s no market for it. Is that there because their culture was against it, or is it because people weren’t pushing it and offering it?”

Ideologies within the Asian community vary visibly along generational lines: from attitudes towards protesting to seeking mental healthcare, one of the challenges now facing young Asian-Americans is educating their elders effectively on the changing tides and temperatures of the country. “When I first brought up the George Floyd incident, the riots, the craziness that was happening that year, my family had this idea of ‘it’s none of our business, it’s not affecting us by any means, we should just keep our heads down and let them handle it,’” said Derrick. “I bring this back up now like, ‘this is happening in our community.’ It’s definitely a culture shock and has forced a lot of people in those older generations to think about it differently.”

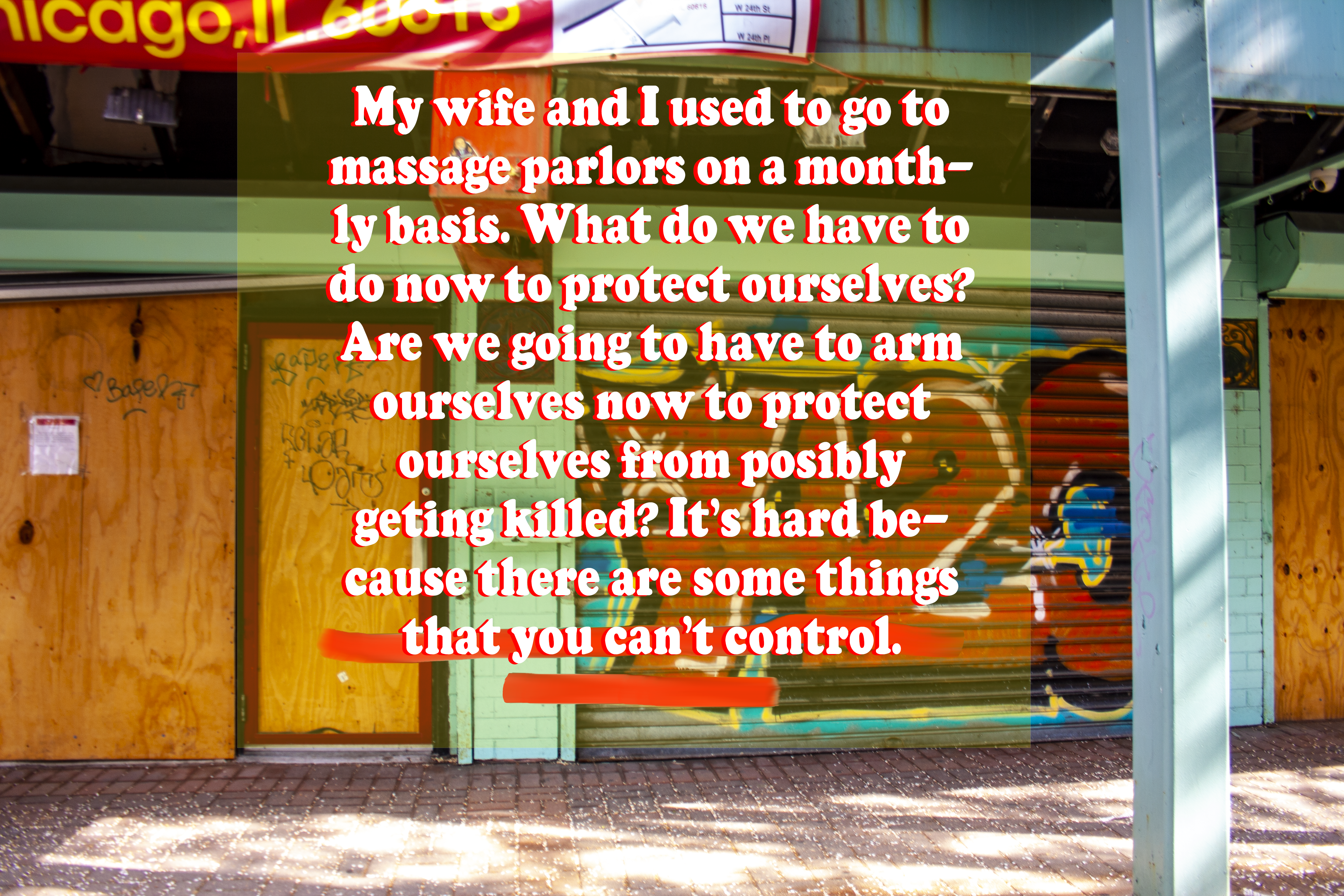

Covid-19 has brought with it many changes to the daily lives of Asian-Americans – some severe, some subtle – and my interviewees all reported increased fear for their safety and the safety of their loved ones. “I worry first about my family, my grandma and my mom that live in the suburbs in a predominantly white neighborhood,” said Derrick. “You don’t know what’s going to happen to them if they go out to the grocery store. My wife and I used to go to massage parlors on a monthly basis. What do we have to do now to protect ourselves? Are we going to have to arm ourselves now to protect ourselves from possibly getting killed? It’s hard because there are some things that you can’t control.”

Bonnie reported an increased awareness of her Asian identity – a shift unwelcome to her. “I never feel self-conscious that I’m Asian or I’m Chinese. I’m just myself. But [at] the beginning of the pandemic when the governor called for shutdown, I sensed that when I walked into my apartment building and went up the elevator, people looked at me differently. And it was an uneasy feeling. I had never felt that way. It’s a thought that I should not have but cannot avoid.”

“I was proud to be Asian back then, I’m still proud to be Asian now. not everybody has the kind of privilege that I had to have that kind of pride, because I know in different areas and different situations it’s been shameful to be Asian,” said Chris. “You talk about the place of the Asian in today’s society, we’re a footnote in somebody else’s story. Regardless of what side you’re on, we’re either a footnote as an ally to black people or we’re a footnote as white-adjacent.”

From the time they arrive in the U.S., Asians are taught by society and in turn teach their children to work hard, get good grades, and keep their heads down. The myth of the “model minority” has homogenized the Asian-American community into a mold of obedient industriousness, one conveniently wedged between the black and white populations to fill a role of perpetual racial triangulation.

But the pandemic has heightened Asian-American Chicagoans’ consciousness of this myth – and galvanized the community into long-overdue rebellion against it.

“I think the solution is not to say “it’s us against them.” It’s to say, “we are Asian-American, we have our own story in this world, we came here and I know we’re not a monolith – every Asian group and individual within those groups is different – but it’s time for us to be telling our own story.”

I wrapped up with Chris and boarded the Red Line back to Hyde Park, turning the interview over and over in my head. I remembered my roommate and I sitting in my dining room the night after Atlanta and asking ourselves – are we even allowed to be scared? Are we Asian enough to tell our parents that we’re worried for them, to be sitting here in shock, to get out into the streets and protest? Are we Asian enough for anything?

To myself I would say now, you are enough. The reason you don’t think so is simply because you are yourself – you were raised Asian, and being raised Asian more often than not means hesitation, submission, assimilation and, like countless others before you, just not ruffling any feathers.

From what my project showed me, the days of feather-ruffling are well underway as Asian-Americans in this city and throughout the country come into their power. On May 20th Joe Biden signed the Covid-19 Hate Crimes Act into legislation, which requires the Department of Justice to expedite the review of pandemic-related hate crimes. On May 31st, Illinois became the first state to require that public schools teach Asian-American history. The Covid-19 pandemic ignited a spark within the Asian-American community of Chicago and beyond that won’t soon be extinguished, and I’m prouder than ever to be a part of it.